Why Nike Ran Back to Amazon—And Why It Scares Every Marketer

How Silicon-Valley Thinking Nearly Destroyed the World’s Greatest Brand

The problem with keeping up with the news is that… you’re always just keeping up with the news. It’s one damn thing after another.

When you’re stuck in the moment, the world starts to look like a highlight reel of random events. One quarter, a company’s the hero. The next quarter, that same company is a zero.

The CEO? He may have been a genius yesterday, but tomorrow he’s an idiot. And no, this isn’t another Tesla rant. Been there, done that.

I’m talking about Nike. That’s a story worth telling now.

After six years of holding out, Nike is crawling back to Amazon. It’s now selling once again on the world’s largest e-commerce platform: a move that screams strategy—and survival.

What happened, and why should every manager be terrified?

Let’s rewind.

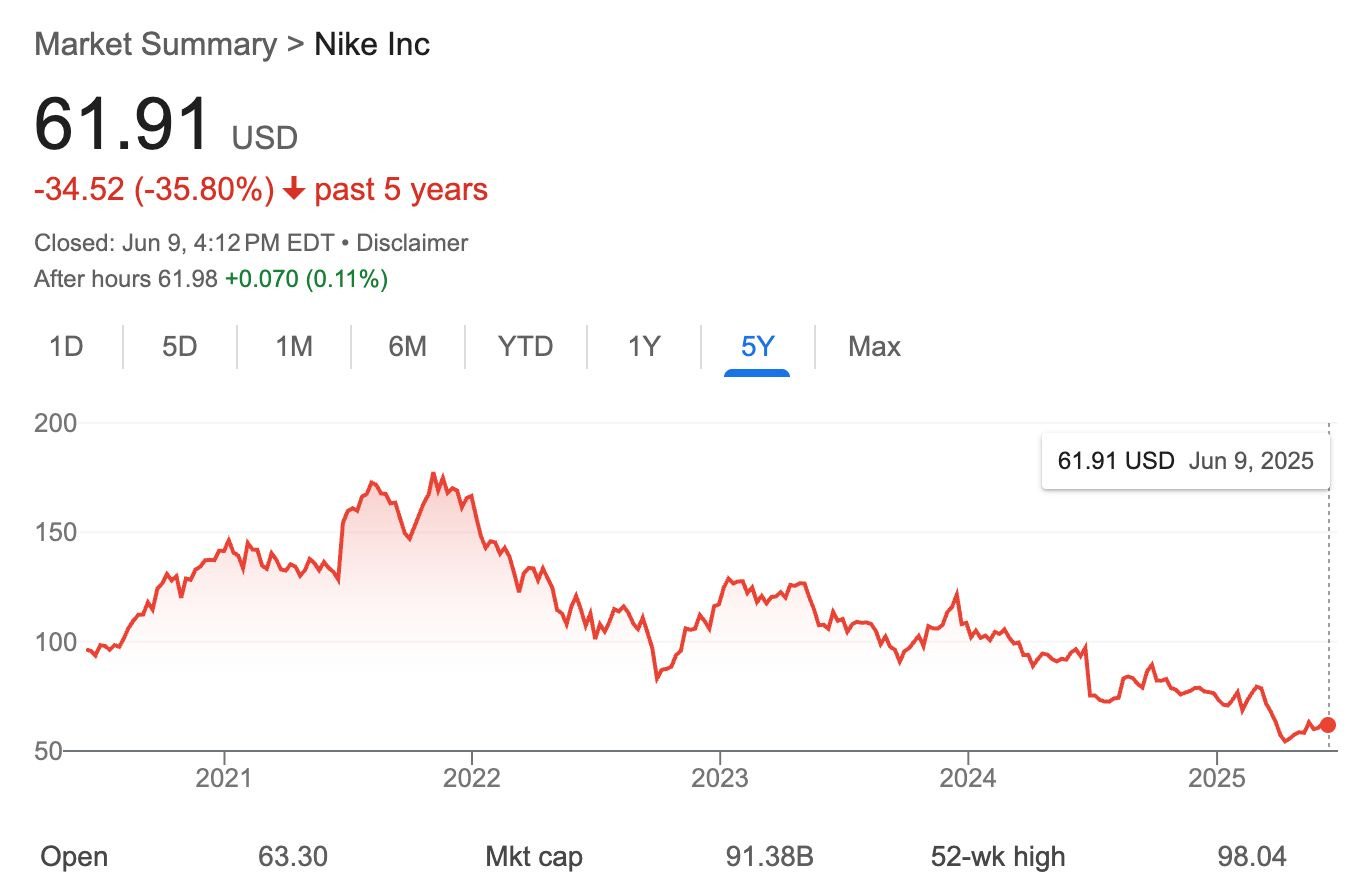

How Nike Fell—In Record Time

In January 2020, Nike handed the keys to John Donahoe. A Silicon Valley veteran (former CEO of ServiceNow, eBay, and Bain), Donahoe wasn’t a shoedog. He was a systems guy.

Nike’s board didn’t want a new vision. What it wanted was speed. Nike’s “Consumer Direct Offense” had been in motion since 2017. Donahoe’s job? Scale it. Fast.

So he got to work. The company pulled back from wholesalers and doubled down on its own stores and apps—just like Disney ditched Netflix to build Disney+.

Why the change? Because direct-to-consumer meant better margins. With more data, the company also had more control. Nike Training Club. Run Club. SNKRS App. These became the core pillars of a new digital Nike.

SNKRS—a sneaker-focused app offering exclusive access to new releases and restocks—became “the crown jewel of Nike Digital.” The app crossed $1 billion in revenue by 2020. It wasn’t just a channel—it was a competitive advantage, according to Donahoe.

The ambition? Predict what consumers wanted—before they even knew it.

Then the pandemic hit.

The world locked down. Nike’s digital platforms took off. Livestream drops in China. Sneaker fever in New York. It wasn’t just a brand—it was a movement. On your phone. In your feed. Everywhere.

Analysts gushed. Investors cheered. Donahoe was hailed as “the right CEO for the digital age.” A tech brain with retail chops.

Everything was working. Until it wasn’t.

Fast forward to today. Nike’s sheen is fading. Sales are slipping. Product buzz is gone. Hoka is taking share. On is surging. New Balance? Legitimately cool again.

And where’s Donahoe? Gone.

The same media that once crowned him “the right CEO for the digital age” is now asking, “Who made Nike uncool?”

When Success Makes You Stupid

John Donahoe wasn't just successful. He was legendary. At ServiceNow, he generated revenues from $100 million to $1.4 billion. At eBay, he doubled revenue and tripled profits.

These weren’t lucky breaks. They were systematic victories in the most unforgiving arena of modern business: digital conversion.

Here’s the flipside of success:

It makes you stupid. Not intellectually—but experientially. Win big in one game, and you start believing every game plays by the same rules.

That’s the real danger in business—and in life: not knowing why you were successful in the first place.

Digital conversion is a very specific game with very specific rules. Once you’ve mastered them, everything starts to look like a conversion problem.

Let me give you an example.

Think about your last holiday search. You Googled “hotels in Barcelona.” The screen lit up with travel blogs and restaurant lists, and perched above it all was an ad for Booking.com.

You clicked on it. Minutes later, you were scrolling rooms, comparing prices, and locking in your stay. The experience was seamless. It was brilliant. It was conversion at its finest.

According to a recent survey, 64% of professionals feel overwhelmed by how quickly work is changing, and 68% are looking for more support to keep up. If you enjoyed this article and it brought you clarity, could I ask a quick favor?

Subscribe now. It’s free and takes just seconds to sign up.

You’ll join thousands of other ambitious managers and CEOs getting exclusive, research-backed insights straight to their inbox. Let’s keep you one inch ahead.

This is a universe governed by the science of the last step. Booking.com doesn’t ignite your wanderlust but harvests it. The desire to sip sangria on Las Ramblas already lives in you. Booking.com’s job is to intercept that desire—and convert it into a transaction. And the platform does so with ruthless efficiency.

That was the world Donahoe knew best.

The Math Behind the Last Click

There’s one more thing about Booking.com—what most people don’t see are the automated bidding algorithms running quietly behind the scenes.

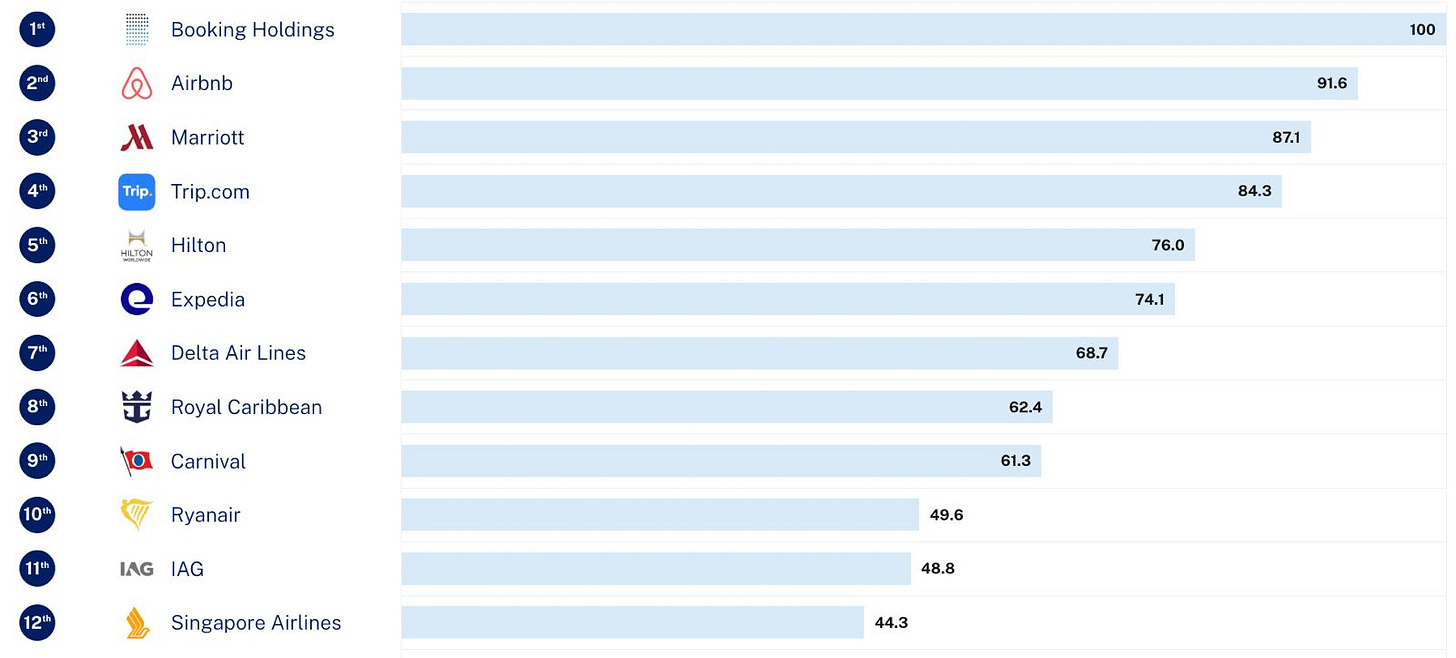

At IMD, where I teach, we recently ranked the most future-ready travel companies. Our composite score blends short-term performance metrics like EBITDA growth with longer-term innovation signals—think geographic expansion, new product launches, and AI adoptions.

The goal? To identify not just who’s winning today but who’s poised to win tomorrow.

Booking Holdings—parent company of Booking.com, Kayak, Priceline, and Agoda—topped our list. (For the full rankings and to see how we sized things up, head over here.)

Then in follow-up interviews, managers at Booking.com walked me through just how sophisticated their algorithms really are. They evaluate hundreds of variables, such as a person’s location, device, time of day, and search history. The algorithms catch your typos (“Bareclona hotels”), dominate the long tail (“pet-friendly B&B rural Provence”), and account for every imaginable permutation of travel intent.

Behind the scenes, millions of ad bids are adjusted in real time. Ads are dynamically tailored. And every click is priced with precision—down to exactly how much the advertisers can pay Google and still turn a profit.

And it works.

In 2024, Booking Holdings beat Expedia on return-on-ad spend in every major region. The company spent $3.2 billion on Google ads—not to inspire but to intercept, arriving at the exact millisecond you’re ready to buy.

Such is the triumph of data-driven mastery. When the customer’s already thirsty, all you need is a straw at the right moment.

When Emotion Becomes Currency

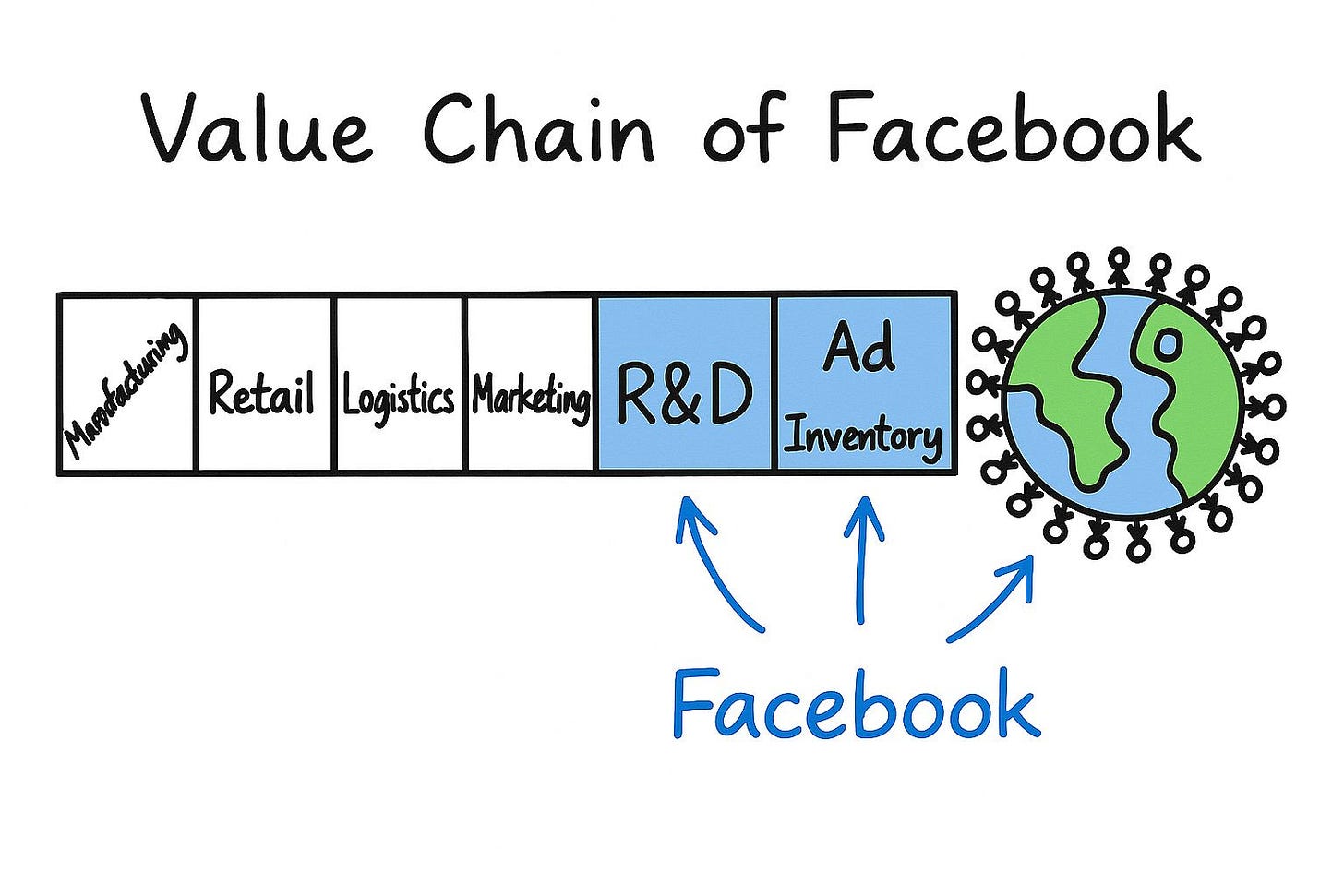

Let’s not forget one thing: This conversion game can get emotional. And that’s by design.1

Facebook keeps you scrolling because outrage drives engagement. Instagram hooks Gen Z for hours because dopamine fuels retention. In April 2017, a leaked internal document revealed something chilling: Facebook was offering advertisers the ability to target users from 13 to 17 years old when they were at their most vulnerable—when they felt “worthless,” “insecure,” “stressed,” “defeated,” “anxious,” “useless,” “stupid,” or “like a failure.”

Instagram and Facebook weren’t just watching. They were mining. Every swipe. Every like. Every selfie, post, DM, even off-platform signal—all of it fed into a system designed to detect emotional dips in real time. One sales deck to an Australian advertiser made it all too clear: emotional surveillance in service of selling.

In ad-speak, your insecurity is a market opportunity. Vulnerability is inventory.

This is the core of our digital economy: Capture desire, amplify emotion, and monetize instantly. Facebook, Instagram, Amazon, Google, TikTok—they all specialize in the final mile of persuasion. Turning impulse into income and friction into cash flow.

And this is the world where John Donahoe came from. It’s where every problem has a technical fix, where A/B testing reveals truth, and where data isn’t just informative—it’s destiny.

And yet, Nike doesn’t live there.

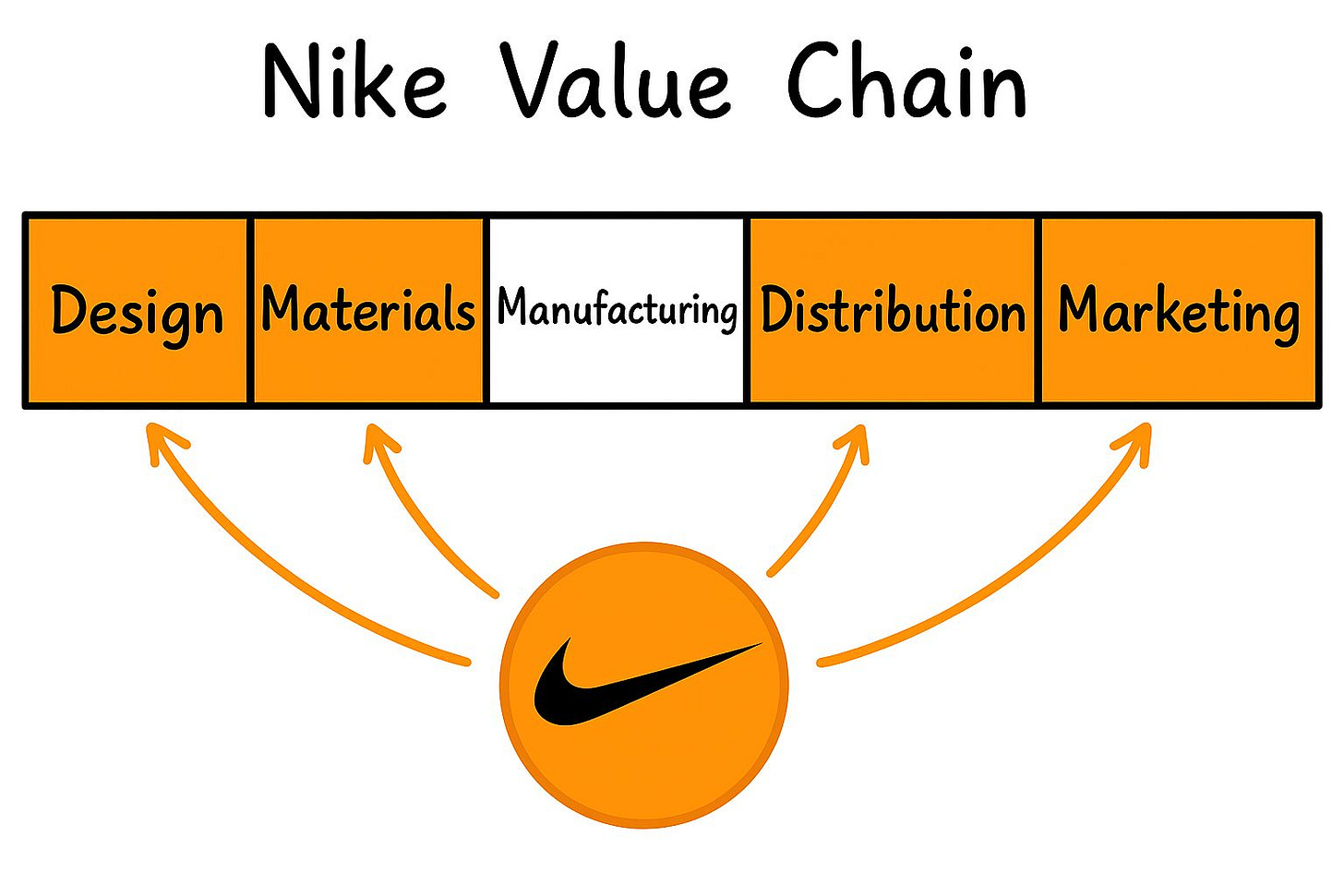

Nike isn’t Booking.com—it doesn’t sell other people’s hotel rooms. It’s not Amazon, either—it doesn’t push someone else’s sneakers. It’s not even PayPal.

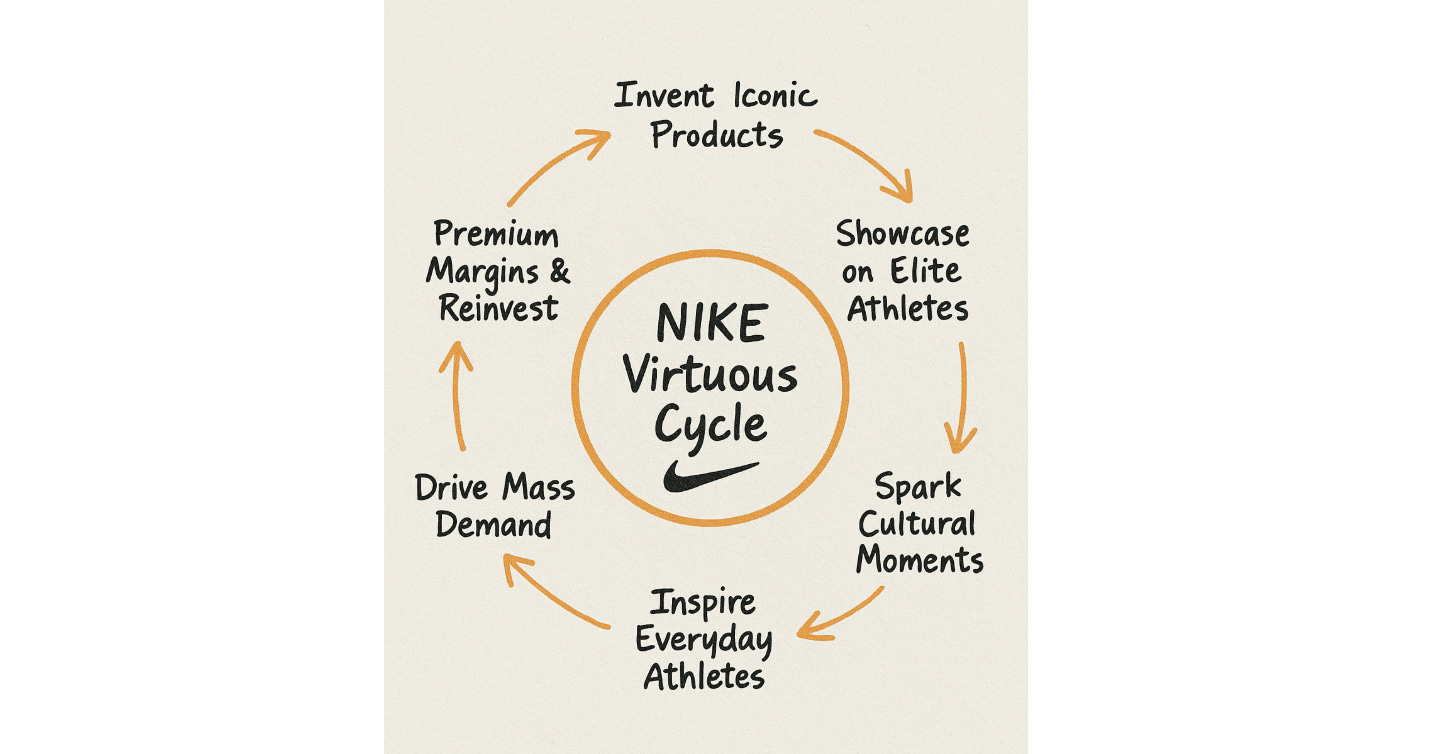

The Two Games That Every Business Must Master

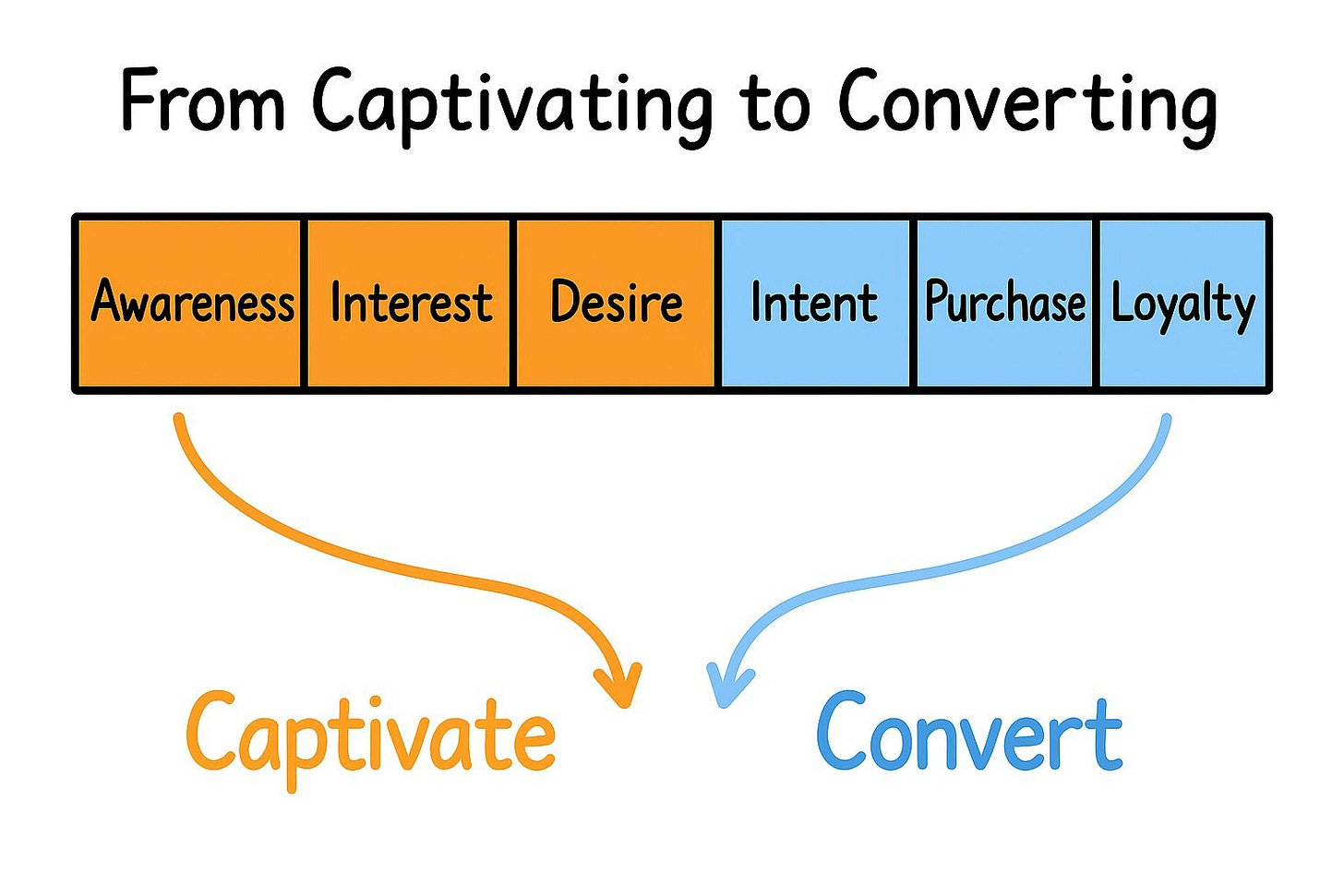

CAPTIVATE: Create desire from nothing. Build mythology. Make people feel something before they buy anything.

CONVERT: Harvest existing desire. Optimize the funnel. Turn intention into transaction with ruthless efficiency.

A seamless checkout will mean nothing if no one burns to buy what you’re selling.

Nike is closer to Hermès. It can’t assume that desire already exists. Instead, Nike has to create the desire.

The Desire Creation Problem

For 50 years, Nike played in the upper funnel, where desire is not captured but created. “Just Do It” wasn’t a checkout prompt; it was a battle cry.

Nobody woke up in 1985 needing Air Jordans. Instead, people woke up wanting to “Be Like Mike.” His impossible dunks made you feel invincible. People saw the swoosh on a friend, on a screen, or on a city street and felt it—long before they ever clicked. Nike wasn’t a transaction; it was a badge of belonging.

That’s brand love. Messy, intangible, human. It’s built with stories, with cultural resonance, with moments that stick. This is the paradox of great brands: They create the very desire that they fulfill.

When John Donahoe surveyed Nike’s wholesale web, he spotted “inefficiency.” Middlemen taking margin. Data that they couldn’t capture. Experiences that they couldn’t control. His Silicon Valley brain said, “Cut them out. Go direct. Own the relationship.”

The pruning didn’t stop there. Inside Nike, Donahoe saw more fat to trim:

Product Categories? Running, Basketball, Football—all those tribal expert teams? Axed.

Six months, hundreds of specialists gone. Thousands of years of foot-strike lore, ankle-support nuance, and boot wisdom—vaporized.

Organizational Structure? Replaced with Men's, Women's, Kids'—retail-generic, Zara H&M sort of divisions.

But the middlemen and the marketers he dismissed weren’t overhead. They were the ones who manufactured mystique.

Walking a kid from Akron to Foot Locker wasn’t “inefficient distribution.” It was like taking him to a temple. Shoes on the wall were possibilities. The associate who whispered, “I saved your size in the new Jordans” wasn’t working for a cost center. Instead, he was practicing evangelism.

What Donahoe “optimized” away:

❌ Category experts with deep, decades-long expertise

❌ Retail partners who acted as brand evangelists

❌ The “inefficient” magic of in-store discoveryWhat he added:

✅ Clean data and direct-to-consumer relationships

✅ Higher margins—at least on paper

The Lesson From Nike’s Lost Soul

Nike’s next act, under CEO Elliott Hill, will test whether the company can reclaim love without losing efficiency. But the drama isn’t just Nike’s. It’s ours, too. In a world obsessed with the last mile, who still dares to run the whole race?

Great companies never pick sides between desire and conversion. They master both. Every name atop our Future Readiness Indicator—L’Oréal, Coca-Cola, Procter & Gamble—pairs downstream precision with upstream seduction. First they captivate, then they convert.

That’s what On understood—and what Nike forgot. While Nike was optimizing digital apps, On laced up at local races. While Nike perfected online friction, On was letting runners feel that odd, cloud-cushion sole on real asphalt.

John Donahoe didn’t fail for lack of brains or resources. He failed because he carried the wrong mental map into terrain that needed a different compass.

In business, catastrophe can come from flawless execution of the wrong idea—like using a street map of Manhattan on an Alpine trek.

The part that matters to all of us is this: The strengths that make us legends in one game can sabotage us in the next. Yesterday’s playbook can become tomorrow’s liability.

Because sometimes, the answer lies not in algorithms but anthropology.

Not in systems but storytelling.

Not in the funnel but the field.

Once algorithms become your only lens, they also become your blind spot.

When Nike traded magic for metrics, it didn’t just cut margin—it severed the nerve that makes people care.

Data alone won’t tell you what you really need to know.

I spend 20+ hours researching and writing each of these pieces — going through academic papers, interviewing experts, and connecting dots others miss, so you don’t have to. If you enjoyed this article and it brought you clarity, could I ask a quick favor?

Subscribe now. It’s free and takes just seconds to sign up.

Not only does it help justify the research time, but as our community grows, I can secure even better access to the executives and researchers who shape tomorrow’s business landscape — bringing those insights directly to you.

Like any researcher, I create content by building on the inspiration of others—standing on the shoulders of giants. And in this case, I want to acknowledge the one and only Ben Thompson and his blog, Stratechery. His recent piece “Nike on Amazon: Nike’s Disastrous Pivot, Inevitability, Intentionality, and Amazon” was a spark that pushed me to dig deeper into an angle I believe is worth exploring.

A great story and lesson for leaders. This was a story about distribution, channels to market, and adding value to a core offer. As Howard says, he missed the core of the proposition - the product. The real thing missing around this is true obsession about the customer from a need, to thinking about purchase options, the purchase experience, and the post-purchase experience. An obsession on the customer covers both the rational and the emotional needs of a customer. If there was a focus on understanding the customer across all the dimensions was better than competition and matched with flawless execution, there would not have been a gap in the growth strategy.

Great post @Howard Yu !! This nails the two-game reality: captivate then convert. Lose either half and the flywheel stalls—no matter how clean your dashboards look.