The Strategy Musk Missed: How BYD Became Tesla’s Nightmare

Once dismissed by Elon Musk, BYD—short for “Build Your Dreams”—outsold Tesla in Europe in 2025. BYD’s slow-burn playbook for domination offers lessons for every business.

In 2011, a Bloomberg TV host asked Elon Musk if China’s BYD could ever challenge Tesla. Musk threw back his head and laughed. “Have you seen their car?” he scoffed.

At the time, BYD hardly seemed like a threat to Tesla.

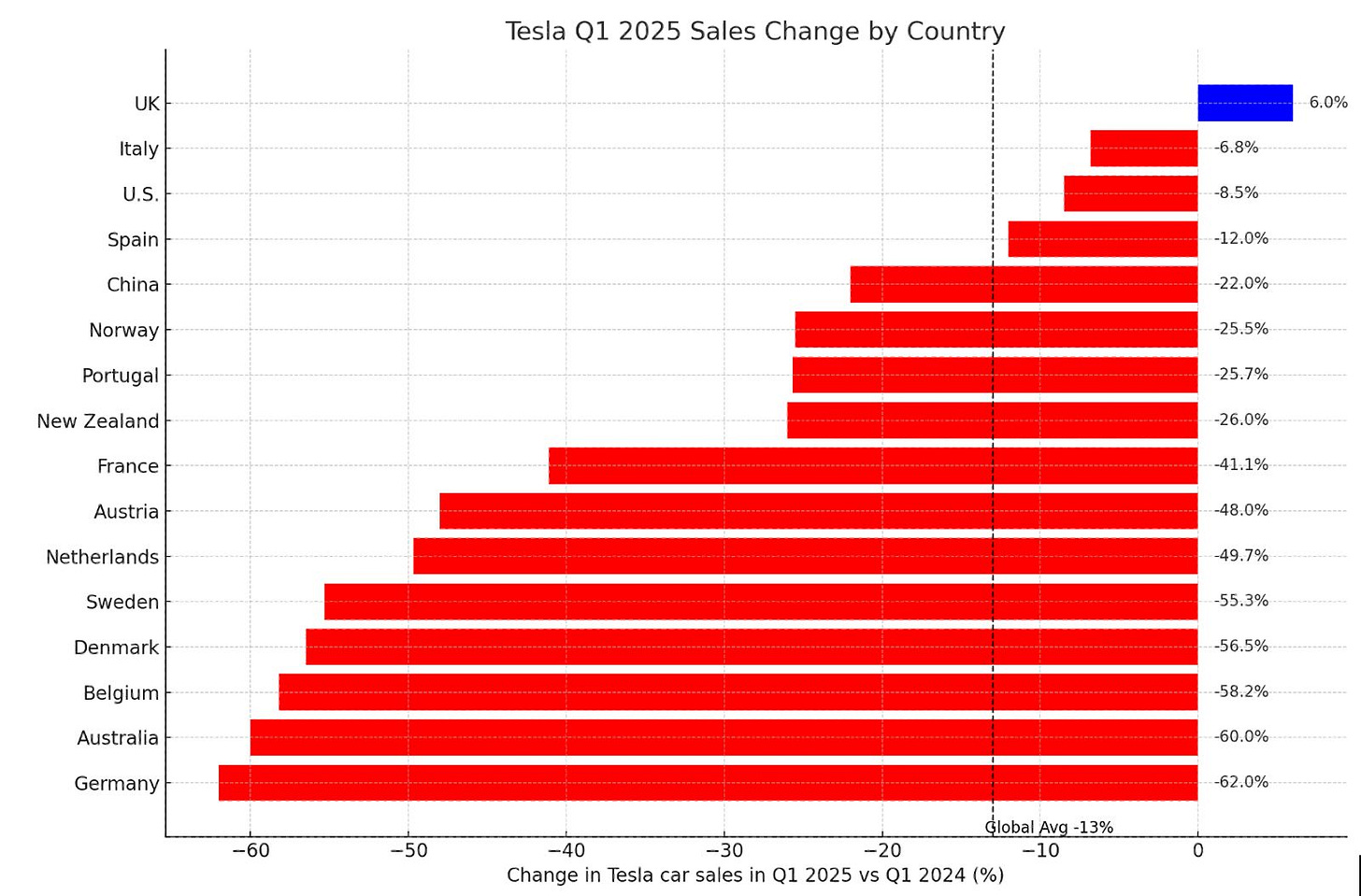

Fourteen years later, the positions of both companies are rapidly reversing. Tesla narrowly maintained its global lead in 2024, selling 1.79 million battery-electric vehicles against the 1.76 million sold by BYD. Despite incurring higher tariff rates than those of Tesla, BYD has also been steadily gaining market share in Europe. Finally, in April 2025, BYD outsold Tesla for the first time.

This saga is important not only for the auto industry. It also demonstrates how strategic patience and compound capability-building are redefining competition. In other words, it’s how the tortoise overtook the hare.

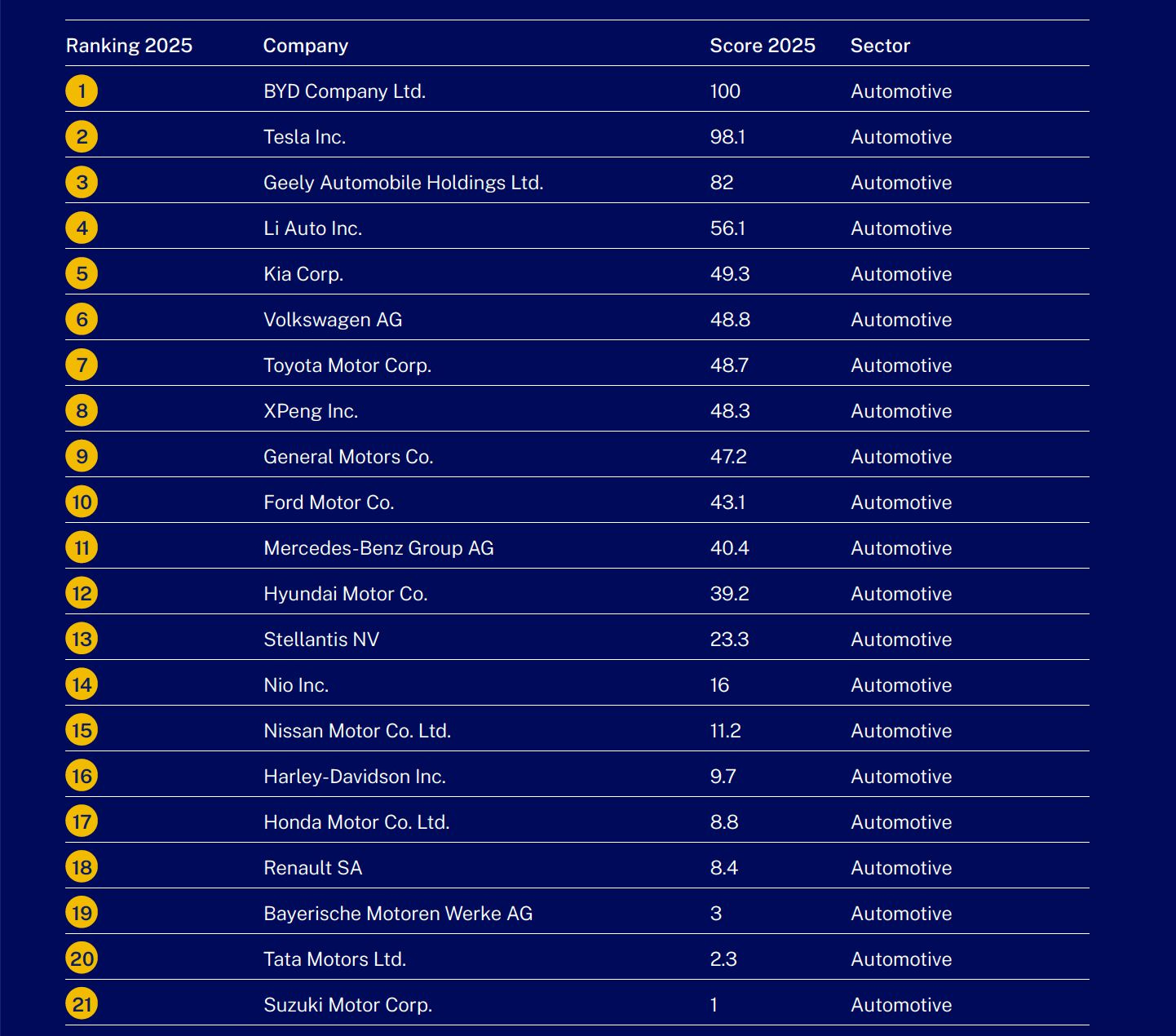

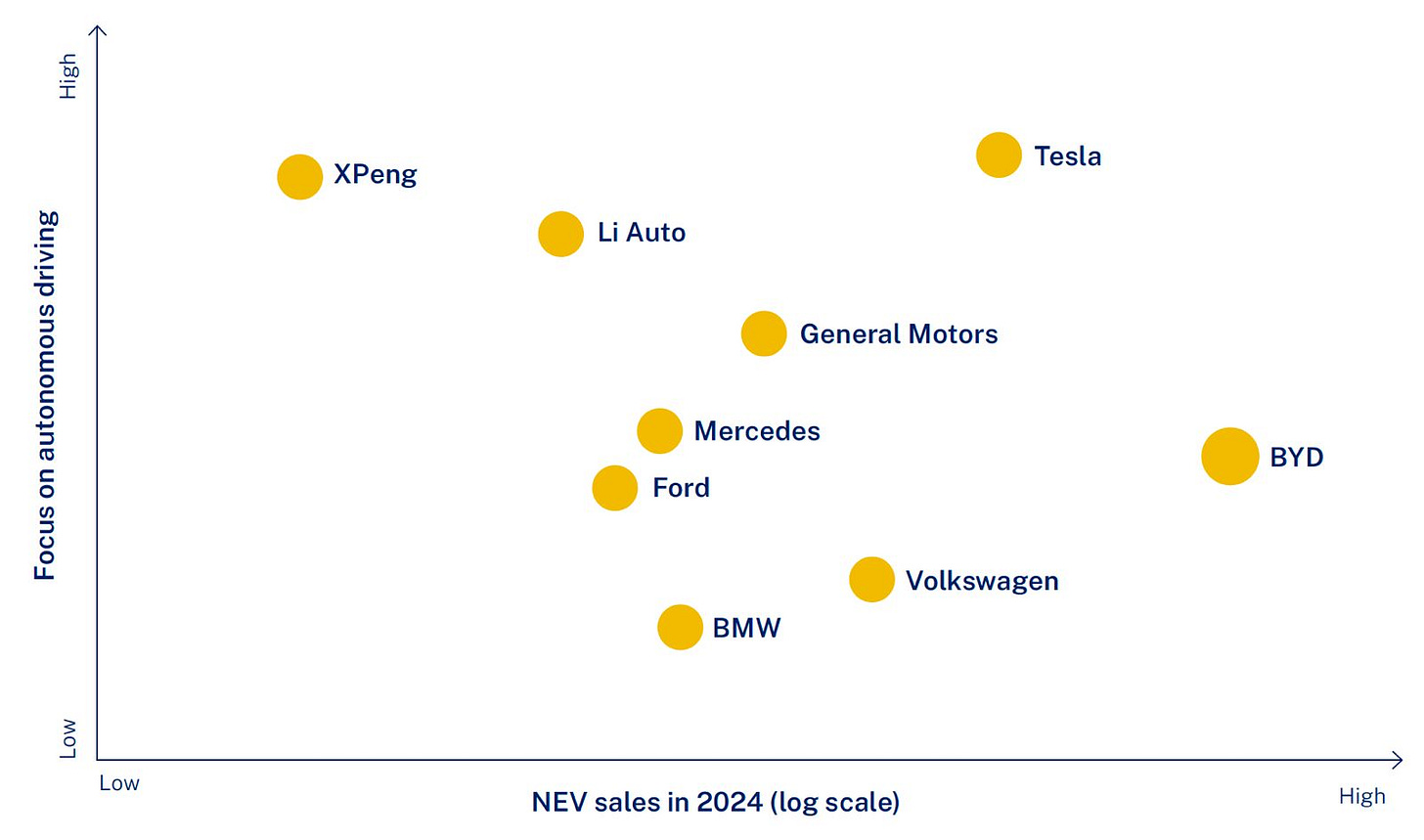

The most remarkable feat is this: BYD pulled ahead while receiving less government support globally than Tesla did. In fact, BYD has now surpassed Tesla in all key metrics—from pure EV sales (on top of a booming hybrid segment) to innovation output.

The company that once drew laughs is now setting the pace for the global auto industry.

How did it happen?

Spotting Winners Before They Win

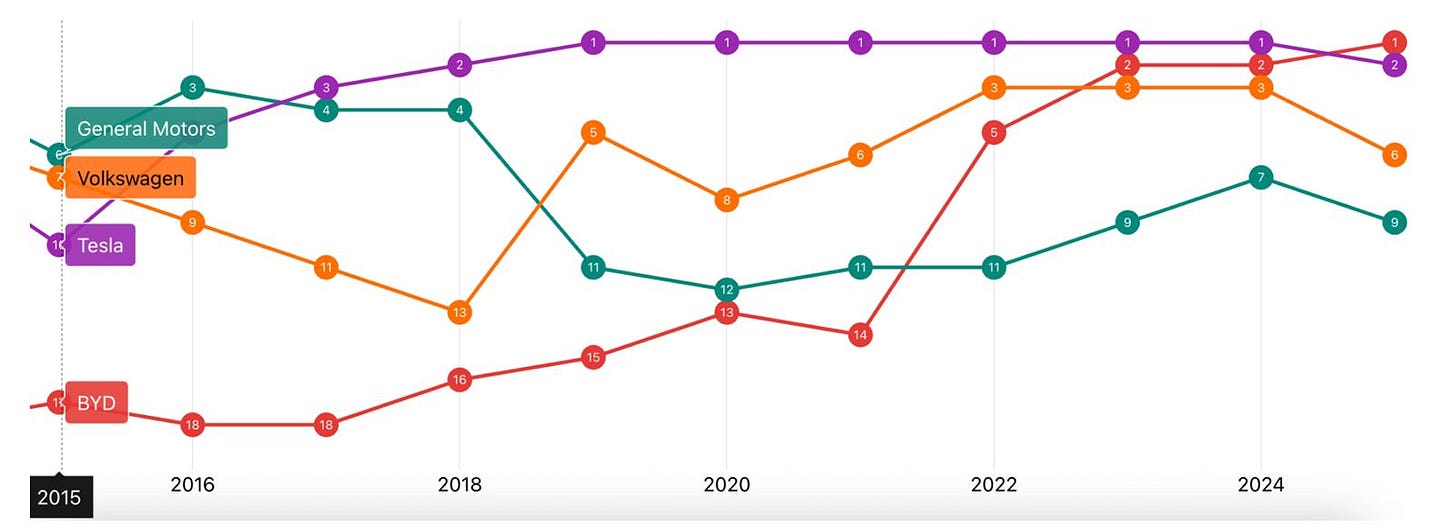

“Only the paranoid survive,” Intel’s legendary CEO Andy Grove once warned. Our latest data shows why. At IMD, we track 300+ companies across seven sectors, watching how giants fall and newcomers rise. Traditional metrics like market share or investor’s expectation are lagging indicators; they only tell you who won yesterday’s race. Our Future Readiness Indicator is designed to spot tomorrow’s winners today.

We analyze everything—from R&D intensity to the speed of innovation deployment and from patent filings to geographic expansion patterns. Think of what we do as a 360-degree checkup on corporate health. And what we’ve uncovered is enough to keep any executive awake at night: In today’s compressed innovation cycles, a company can go from leader to laggard as soon as it is no longer relentless.

This brings us back to Musk’s 2011 laugh: Future readiness is a moving target—and complacency is fatal.

How BMW Built the Future—Then Abandoned It

In the world of electric vehicles, neither Tesla nor BYD were the first movers.

As early as late 1990s, GM produced and commercially leased the all-electric EV1. Toyota launched the RAV4 EV. And BMW rolled out the futuristic i3.

Have you ever seen a BMW i3? It’s actually been around for quite a while. I first spotted one at Munich’s BMW Museum—which, by the way, with its not one but two massive rotundas, feels like the Guggenheim of the car industry.

I remember walking the spiral ramp all the way to the top floor, where a themed area showcased about 30 interactive stations. They offered a vision of a zero-emission, self-driving future. It was pure sci-fi. But it was also real.

One story stuck with me: Back in 2007, then-CEO Norbert Reithofer challenged engineer Ulrich Kranz to “rethink mobility.” A skunk-works team was born, touring 20 megacities, building carbon-fiber prototypes in a garage-like lab, and quietly launching the award-winning i3—two full years before Tesla rolled out the Model S.

We’re not talking about some vague concept car. The all-electric “i3 people mover” that gleamed under white lights at BMW World had a compact hood and a plastic-framed front grille that looked like a pair of Ray-Bans.

When the i3 finally hit the market in 2014, Tesla’s Model S had been on U.S. roads for only about a year. And BMW was racking up accolades—the i3 won the World Green Car award, an achievement that was given to the sleek i8 a year later.

In short, BMW wasn’t just early. It was fast, bold, and ahead of the curve—well before the EV upheaval became inevitable.

Then the project stalled. Silence.

$3 Billion Lesson in Lost Momentum

Project i quietly faded from prime-time TV spots and was eclipsed by BMW’s flashier sports models. No one officially killed it—but inside the company, all eyes turned to “safe” profits. Profit-hungry silos choked off Project i’s funding. Morale plummeted. Factories reverted to churning out gasoline sedans and SUVs.

As BMW i slowed to a crawl, the brain drain was swift. Ulrich Kranz left for Faraday Future. Development chief Carsten Breitfeld became CEO of China’s Byton. Key designers scattered to rival EV startups. BMW’s own innovation team ended up building the competition.

The lesson?

Without sustained resource allocation, even brilliant moonshots wither.

We may never know exactly how much Project i cost. But BMW’s own figures reveal that the carbon-fiber production and autobody work for the i3 alone set them back half a billion euros. When you factor in R&D, marketing, and manufacturing? Easily two to three billion euros—enough to develop two or three generations of the VW Golf or Mercedes S-Class.

To put it in perspective, that’s 15 times what Apple spent developing the original iPhone. BMW burned that amount on Project i, with little to show for it.

Meanwhile, Tesla sped ahead.

While Tesla Partied, BYD Studied

As BMW pulled back and Tesla surged ahead, a third player was quietly building the muscle that would upend them both.

BMW’s misstep wasn’t lost on BYD founder Wang Chuanfu. Bold innovation isn’t enough—it has to be matched by relentless, methodical execution.

Tesla and BYD couldn’t be more different.

According to a recent survey, 64% of professionals feel overwhelmed by how quickly work is changing, and 68% are looking for more support to keep up. If you enjoyed this article and it brought you clarity, could I ask a quick favor?

Subscribe now. It’s free and takes just seconds to sign up.

You’ll join thousands of other ambitious managers and CEOs getting exclusive, research-backed insights straight to their inbox. Let’s keep you one inch ahead.

Full of flash, disruption, and Elon’s spectacle, Tesla exploded out of Silicon Valley in 2003—the Roadster, the Model S, the live-streamed drama.

BYD, in contrast, began in 1995, deep in the industrial sprawl of Shenzhen. In its early days, BYD was cranking out rechargeable batteries for phones and electronics. When Musk was hosting splashy launch events, Wang Chuanfu was tweaking battery chemistry formulas. While Tesla made headlines with the Roadster, BYD was quietly working with Nokia and Motorola.

Throughout the late 1990s, BYD rose to become a leading supplier of consumer batteries. But by the early 2000s, the market was maturing fast—and margins were thinning. Wang Chuanfu was searching for the next growth.

He found it on two wheels.

From Phone Batteries to E-Bikes

In southern Chinese cities, the 2000s brought an explosion of simple, battery-powered bikes and scooters—cheap, practical, and perfect for jammed urban streets. Other dense cities across Asia followed suit.

Taiwan rolled out incentives for e-scooter adoption. By the late 2010s, Bangkok had embraced shared e-scooter fleets.

Building millions of battery packs for bikes and scooters gave BYD a crash course in real-world durability. The company learned how to lower unit costs, extend battery life, and scale manufacturing under pressure.

Then Wang spotted an even bigger canvas: fleets.

The Bus Stop Nobody Saw Coming

BYD didn’t chase luxury sedans. It went after the workhorses—buses, taxis, delivery vans, and trucks. In 2010, it rolled out its first all-electric bus: the 12-meter K9. The timing was perfect. Shenzhen, BYD’s hometown, was preparing to host the 2011 Summer Universiade and needed clean public transport. BYD seized the moment, pushing a bold “Public Transportation Electrification” strategy.

The company deployed 200 K9 buses for the games, making it the first in the world to commercialize electric buses at scale.

That success became a blueprint. BYD buses quietly spread through Chinese cities like Beijing, Guangzhou, and Hangzhou. In 2018, DHL began using BYD’s T3 electric vans in Shenzhen for last-mile delivery. By 2019, BYD had built 50,000 electric buses that served over 300 cities worldwide.

Crucially, this wasn’t just market expansion—it was capability expansion. BYD doubled down on vertical integration: designing and manufacturing its own batteries, motors, and electronic controls in-house. Engineers had to master every nut and bolt. Where others saw scraps, BYD saw strategic ground. It quietly dominated the niches that everyone else ignored.

Copy, Then Improve

When launching the e6 electric vehicle—first as a taxi, then for consumers—BYD wasn’t leaping into EVs like a startup. The company was extending a system of capabilities that it had spent fifteen years quietly perfecting.

This is the classic playbook of low-end disruption.

Each rung wasn’t just a win; it was a learning platform for the next win. Batteries taught BYD about energy storage. Scooters taught the company how to build efficient electric drivetrains. Buses demanded system integration at scale.

Each step up the value chain was built on the last, creating what people call cumulative advantage.

In an industry obsessed with chasing the next big thing, BYD focused on mastering the boring stuff first.

Gigafactories Meet Megacities

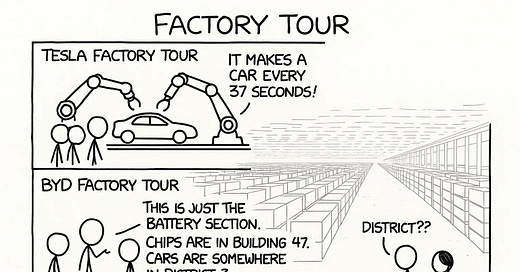

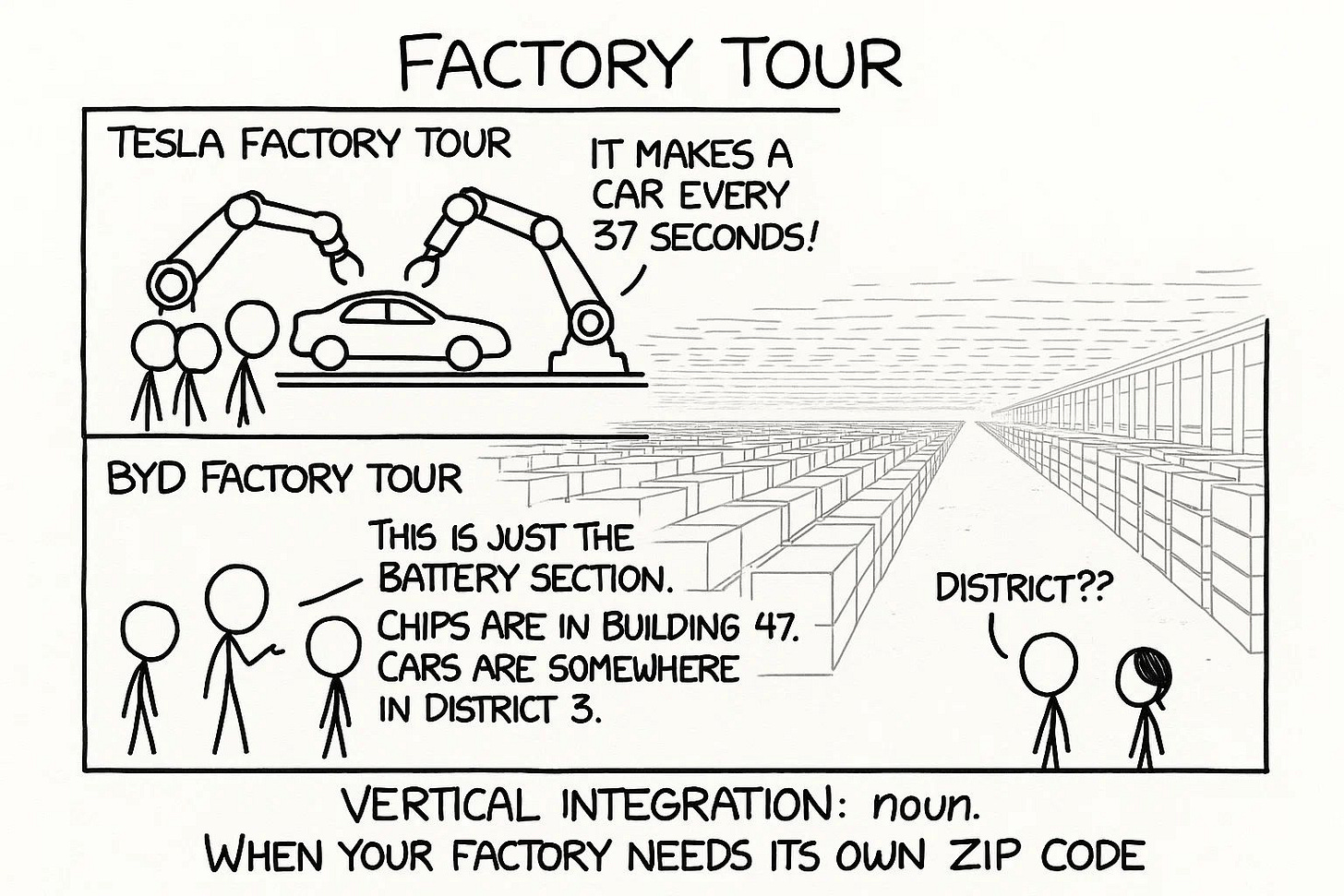

My colleague Mark Greeven recently toured BYD’s manufacturing complex—and came away stunned. He had also visited Tesla’s Gigafactory in Shanghai just months earlier, giving him a rare, firsthand comparison between the two locations.

Mark is Dutch, but his Mandarin is sharper than mine—less Cantonese accent, more fluency. As a result, he captured nuances that I might’ve missed.

At Tesla, he saw the “Musk method” in full swing. The Shanghai Gigafactory is a marvel: a massive structure built in just twelve months and spitting out one car every thirty-seven seconds. Tesla used a “hybrid automation” approach—95% automated but with humans handling specific tasks for which people still outperformed robots. It’s what enabled Tesla to scale fast while adapting to local realities.

One detail stuck with Mark. During lunch, he saw a line worker who was writing C++ code. He wasn’t a manager but a factory-floor operator. “Elon always says, ‘Show me your code, and if it’s good, you have a future at Tesla,’” the guy said.

Impressive, yes.

But then Mark visited BYD—and what he saw there made Tesla’s factory feel almost small.

(He also writes a sharp newsletter called Red Thread on China’s global influence—you can subscribe here if you haven’t already.)

Inside the Machine That Builds the Machine

The Shenshan park already spans 3.79 million square meters (40.8 million square feet)—four and a half times the footprint of Tesla’s Shanghai plant—and BYD has permits to keep expanding. The area even includes an employee village, complete with football pitches and tennis courts.

But this isn’t just a car assembly site. BYD casts its own motors, laminates Blade Battery cells, prints circuit boards, and presses power-module wafers, designing its own IGBT and SiC chips through BYD Semiconductor, located just a few hundred meters from the main vehicle line.

Inside the battery wing are fewer than a dozen people overseeing an entire production hall. The Blade line operates with about 50 workers per gigawatt-hour—just one-fifth the labor required at a typical Western battery plant. Autonomous mobile robots shuttle trays between coating, calendaring, and formation stations. Overhead, warehouse drones scan QR codes to reorder stock automatically.

Nevertheless, people haven’t disappeared. In final assembly, technicians are still tweaking torque programs on the fly—a kind of flexibility that Tesla had to learn the hard way during its Model 3 “production hell.” And in areas where manual labor still matters, BYD has begun deploying UBTech’s Walker S1 humanoid robots to tighten screws, haul bins, and run end-of-line visual inspections. The current goal is a 70/30 robot-to-human split.

The message is unmistakable: The machine that builds the machine now speaks Mandarin.

Where Tesla encourages line workers to code, BYD emphasizes executional excellence, vertical integration, and scientific precision. Its leadership style is low-key, grounded in industrial design and systems thinking.

While Musk made headlines, Wang built everything else. The future wasn’t hyped into existence—it was engineered.

The Factory That Will Swallow San Francisco

And if Shenshan feels immense, BYD’s next move borders on surreal: a greenfield megacampus in Zhengzhou planned to span nearly fifty square miles—larger than the entire city of San Francisco and ten times the size of Tesla’s Nevada Gigafactory. The new location is projected to produce a million vehicles per year and include its own deep-water port.

In 2011, when Musk laughed at BYD’s cars, he was looking at the surface. What he missed was the iceberg beneath—fifteen years of accumulated capabilities, millions of batteries tested, thousands of buses deployed, and a manufacturing system that could scale beyond anything that Silicon Valley had imagined.

The lesson for every business is this: In an era obsessed with disruption and moonshots, BYD’s methodical march is a reminder. Sustainable advantage often comes from mastering the boring stuff.

The Unsexy Truth About Building Futures

The next time someone mocks your unglamorous market or utilitarian product, remember—the future isn’t always built in a garage. Sometimes, it’s built in a factory that no one’s watching, one capability at a time.

The last laugh, it turns out, belongs to those who master the fundamentals first.

Surprised not to see Xaomi Car on the list of "Future Readiness Indicator" -