Excellence Kills, Capabilities Save.

How Yamaha, BYD, and Nvidia build a stack that keeps them future-ready

The night before I went on stage at Nordic Business Forum, I couldn’t sleep. Then I worried about not sleeping enough for the stage. Seven thousand five hundred people. One shot. All I could think about was a floppy-disk keyboard my parents bought me when I was seven in Hong Kong. It’s an instrument that no longer exists, made by a company that prospers by making its own product obsolete.

I never thought I’d tell this story in public, but I did. As Steve Jobs reminded us, “You can only connect the dots looking back.” That electronic keyboard taught me the most expensive lesson in business: Mastery without evolution is extinction.

My mother wanted me to learn piano as a child, but the class was full. So she signed me up for Yamaha’s Electone. My parents scraped together HK$60,000 for this two-keyboard, foot-pedal contraption that loaded songs with floppy disks.

I played that thing until I could make it sing.

Today, that Electone belongs only in a museum, right beside fax machines and cassette tapes. Yamaha has practically innovated my instrument out of existence! Yet the company went on to dominate digital keyboards, guitars, and concert pianos. It did well.

That single childhood experience planted in my mind a question I have pursued throughout my career: Why do some companies reinvent themselves while others fade away?

Here’s what I told the audience that day. The companies that die don’t lack excellence. Kodak perfected film. Blockbuster perfected stores. Steinway perfected pianos. They declined because they perfected the wrong thing. They optimized for today while tomorrow was already here.

What, then, about the companies that prosper?

They don’t perfect products. They collect capabilities.

How? Three principles:

Perform and transform, simultaneously;

Own your learning, and show it;

Make yourself ridiculously easy to work with.

Over the past five years, at IMD’s Future Readiness Center, we are obsessed with the question I’ve pondered since childhood. We’ve analyzed hundreds of companies across seven industries — from cars to tech to fashion — tracking who turns crisis into opportunity. We are nerdy enough to build a Readiness Indicator to rank firms.

And the more I’ve spoken with people in hallways, classrooms, and conferences, the more they’ve made me see how these lessons apply not just to corporate strategy but to personal growth.

So let’s unpack.

Perform & Transform: The Steinway / Yamaha Lesson

Let’s be honest: Steinway makes the world’s finest concert grand. Period.

Those pianos are coveted by maestros and have stood on the stages of Carnegie Hall and the Smithsonian. Arthur Rubinstein once said, “A Steinway is a Steinway and there is nothing like it in the world.”

But mastery alone doesn’t guarantee prosperity. When industry knowledge matures, copycats catch up.

Steinway’s sales peaked at 6,000 pianos in 1926. By 2012, sales had dropped to just over 2,000. The company changed hands multiple times, sold off land, and was reduced to a single workshop in Queens, New York.

Despite being world-class in what it does, business dwindled.

Across the Pacific, Yamaha was doing something far less glamorous.

Post-war Japan needed compact upright pianos for small apartments. Yamaha automated production, cutting variation to near zero. Robots sorted veneer. Hydraulic presses shaped rims in minutes. Just two workers guided each piano through the line. By 1966, Yamaha was the world’s largest piano maker, producing 200,000 instruments a year compared to Steinway’s 6,000.

(This is a textbook case of low-end disruption. Here is a longer piece that unpacks the framework of disruptive innovation in detail.)

Profits from those humble uprights funded Yamaha’s research into concert grands. They began to reverse-engineer Steinways: It bought their pianos, tore them apart piece by piece, and studied every component until Steinway’s CEO admitted Yamaha knew their product better than Steinway did.

Then it went further. Yamaha sponsored artists and pampered opinion leaders. They rolled out red-carpet VIP service, from helping leading pianists choose an instrument in the showroom to delivering it straight to the concert hall, all free of charge. It was creating a cultural phenomenon.

Finally, Yamaha released digital pianos that replicated Steinway’s sound at a tenth of the price. While Steinway was sold to private equity in 2013, Yamaha became a global powerhouse.

Yamaha wasn’t doing random things. It was systematically collecting new capabilities to stay relevant.

The lesson?

Perfecting today’s core offering is never enough. That’s the paradox of perform and transform. Delivering today while building for tomorrow is not a tradeoff.

Never stand still. Rivals will scale if you don’t.

Which brings us to the second principle: Transformation isn’t just about what you build. It’s about how you learn.

According to a recent survey, 64% of professionals feel overwhelmed by how quickly work is changing, and 68% are looking for more support to keep up. If you enjoyed this article and it brought you clarity, could I ask a quick favor?

Subscribe now. It’s free and takes just seconds to sign up.

You’ll join tens of thousands of other ambitious managers and CEOs receiving exclusive, research-backed insights delivered straight to their inboxes. Let’s keep you one inch ahead.

Own It, Show It

Many firms still treat transformation as a single bet on a dazzling new product after months of analysis. That rarely works.

I had a side chat during the conference with Risto Siilasmaa, a former board member and later CEO of Nokia, the man who pulled the company back from near bankruptcy after it jettisoned its mobile-phone business and re-emerged as a global network player.

Risto told the audience, “No bad news is bad.” In other words, if you don’t hear bad news, it means people are hiding problems instead of surfacing them.

And how can I not agree? That culture of transparency is the foundation of any learning organization. Since no company gets things right from the start, the winning companies aren’t those armed with the perfect idea on day one. They’re the ones that let bad ideas fail faster.

You have to show both failures and successes without blame.

Take Booking Holdings, owner of Booking.com, Priceline, and Kayak. They built a system where every campaign, ad, and feature is tracked in a centralized database. Everyone across all levels can see what works and what doesn’t. Successes and failures are both captured and shared, not swept under the rug. Show them.

That kind of transparency explains why they ranked at the very top of the industry. (Here is an in-depth readiness analysis of the global travel industry, with all the relevant players ranked.)

Risto Siilasmaa, now an investor and board member of numerous tech companies, offers another reminder: Momentum matters. Winning organizations experiment, scale, and keep going.

I can see this in BYD, the Chinese company that just edged out Tesla to top our Future Readiness Indicator. Founded in 1995, BYD started not as a carmaker but as a producer of rechargeable batteries for mobile phones. When that market became crowded, founder Wang Chuanfu asked a simple question: What else needs batteries?

In the 2000s, as Asia’s cities filled with battery-powered bikes and scooters, BYD pivoted. It produced millions of battery packs for them. That small shift set the stage for something far bigger: electric cars.

Building those packs taught BYD how to lower costs, extend range, and scale manufacturing. (Here’s a longer analysis on how BYD has become Tesla’s biggest nightmare.)

Then, instead of going after luxury sedans, it targeted buses, taxis, and delivery vans. The workhorses of transport.

In 2010, BYD rolled out the 12-meter K9 bus, becoming the first company to commercialize electric buses at scale. By 2019, it had built 50,000 electric buses serving more than 300 cities worldwide.

Each step up the value chain built on the last. Batteries taught energy storage. Scooters taught efficient drivetrains. And buses demanded systems integration. BYD doubled down on vertical integration, designing and manufacturing its own batteries, motors, and electronics.

These capabilities weren’t random. They were steppingstones. Own them.

So when BYD finally entered the passenger-car market, it wasn’t a scrappy startup. It was already a vertically integrated powerhouse. Today it’s the world’s #1 EV seller. That patience and capability-building over 25 years allowed BYD to finally surpass Tesla.

Future readiness is never a finish line.

It is a work in progress. If you don’t move forward, others will catch up. But setbacks are not permanent either.

You can turn things around, unless you wait too long.

And here is where the third principle comes in: You can’t do it all alone. You always need help from the outside.

Nvidia’s Zero-Billion-Dollar Bet Against Intel

The third principle is simple: Make yourself ridiculously easy to work with. Great companies don’t try to do everything alone. They build platforms that invite others to innovate on top of them.

Nvidia is a master at this. It began as a graphics card maker for gamers, designing chips that excelled at parallel processing. Rather than guard its technology, the company invested more than $10 billion to develop CUDA, a programming model that let developers deploy the GPU power any way they want.

And then they made CUDA freely available.

CEO Jensen Huang called it a “zero-billion-dollar” strategy because there was no obvious market at the time.

But by making its platform open, Nvidia ignited an explosion of innovation. Researchers used GPUs to train neural networks. Tech giants improved machine translation. Scientists applied them to everything from weather models to financial simulations.

Once developers built on CUDA, switching costs soared, cementing Nvidia at the center of the AI revolution.

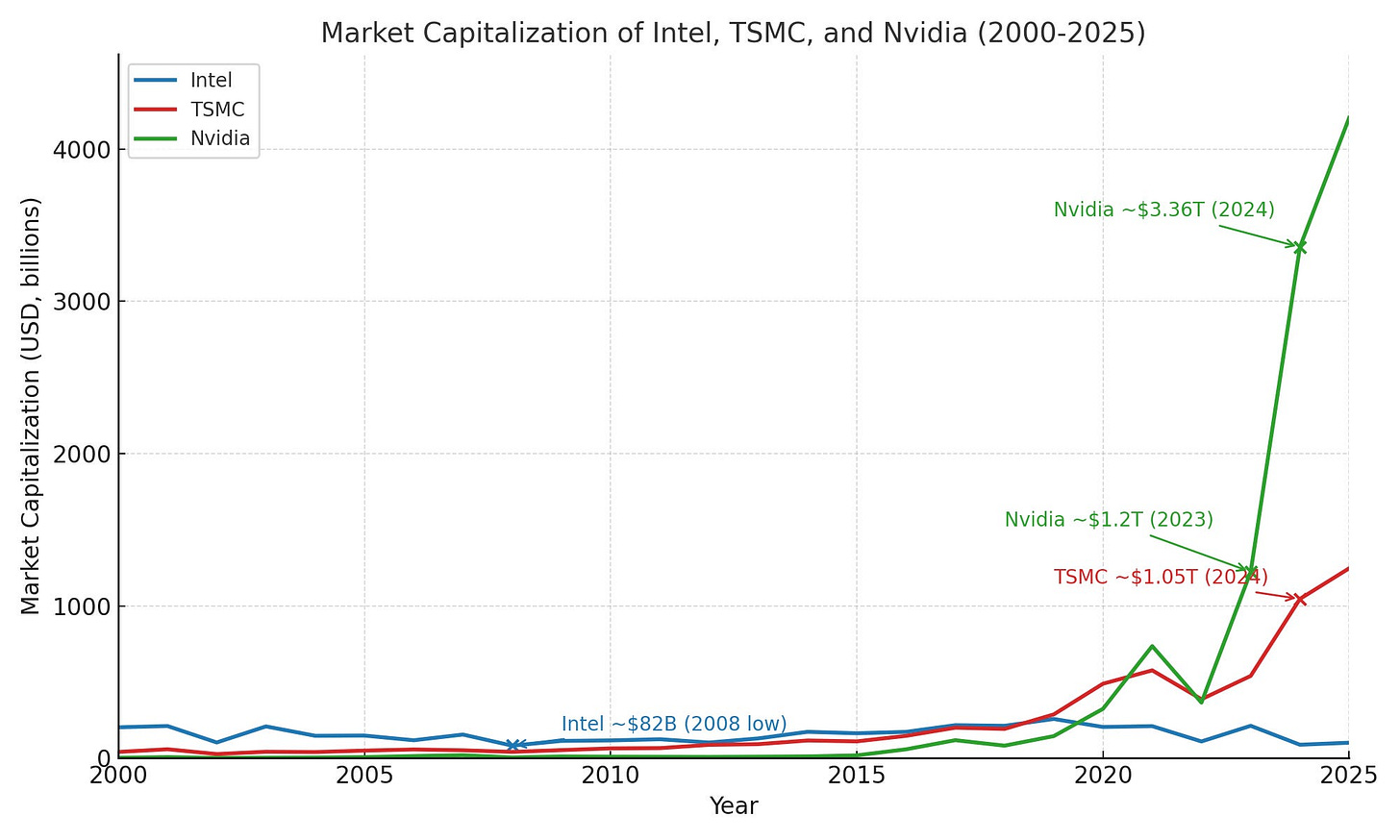

(And, of course, you cannot talk about Nvidia without mentioning TSMC. I’ve written a longer piece on how TSMC added more market cap than Intel ever lost.)

The lesson isn’t to give away your crown jewels blindly.

It’s to ask how easy it is for customers, suppliers, startups, or even colleagues to plug into what you do. APIs, hackathons, open datasets, and cross-functional sandboxes lower barriers to collaboration.

When the outside world can extend your capabilities, your company becomes a platform rather than just a product.

This principle isn’t only corporate. It applies to us as individuals, too.

Easy to Work With: The Rick Rubin Angle

At the closing session in Helsinki, we had Rick Rubin on stage. I know... crazy.

Someone asked him: How do you resolve differences between artists you work with? He said the trick is to change the conversation, from “I disagree” to “let’s build it.”

Often, Rubin explained, what one person imagines is very different from what another envisions. He once told an artist that a transition in a song didn’t work. The artist replied, “We’ll just cut that part in half.” Rubin thought to himself, “What a dumb idea.” But instead he said, “Let’s try it.”

The artist played it, and it worked.

Rubin added one more insight: when you turn an idea into something tangible — a model, a demo, a prototype — it releases the idea from the person. It becomes objective. Then people can say, “This part needs a tweak,” instead of, “You’re wrong.” The conversation shifts.

He even said, “If there’s disagreement, I always side with the artist’s vision. Because to them, it’s their career. To me, it’s just one piece of my portfolio.”

Here is a legend who makes himself very easy to work with.

Be One Inch Ahead

The pattern? Steinway perfected pianos. Sold to private equity. Kodak perfected film. Lost 90% of its workforce. Blockbuster perfected stores. Bankruptcy.

In contrast, Yamaha collected capabilities. BYD collected capabilities. Nvidia collected capabilities. All are thriving.

Your core competency is what you are good at today.

Your capability stack is what saves you tomorrow.

Stop perfecting. Start collecting.

“What’s needed?” you may ask. Steady execution, aggressive learning, and a porous culture that invites others in.

The most resilient organizations avoid the pendulum swing between austerity and indulgence. They treat learning as a muscle, not a one-off.

That’s why, whether you are running a multinational or mapping your own career, ask three questions:

Am I performing and transforming?

Like Yamaha, am I investing in tomorrow’s skills while delivering today?

Am I owning my learning?

Like BYD, am I building on my core, experimenting relentlessly, and scaling what works?

Am I easy to work with?

Like Nvidia, does my platform invite others to innovate

The answers will determine if you stay stuck or move ahead.

At Nordic Business Forum, I learned from other people’s craft, and I learned something about myself too.

Backstage in Helsinki. The lights blazing, the crowd buzzing. Seven thousand pairs of eyes waited. My chest tightened. Public speaking at this scale? Never done it before.

But here’s the thing about being future-ready: It’s not about being fearless. It’s about being one inch braver than yesterday.

That’s what I learned from studying hundreds of companies, and from showing up anyway.

No one needs to transform overnight. Get one inch ahead of the past. The future belongs to the ready. It is an adventure.

See you in two weeks! 👋

P.S. In 2026, Oprah will be there. That’s right, Oprah Winfrey will be a speaker. It’s amazing the Finns pulled it off. Not London, not Paris. But Helsinki.

And here’s a little gift from my school, IMD. If you’ve enjoyed my pieces so far, you’ll find even more great content at I by IMD. Just scan the QR code below to get a three-month subscription for free. 🎁

One more bonus: if you want to hear a podcast right after my talk at the conference, here it is! I’m joined by another amazing speaker, Peter Hinssen. He’s not only sharp, he’s very funny too. You can listen on all platforms by clicking here.

Thank you Al! I am so glad that this piece resonates. It feels a little scary to write out my own internal feeling. But so happy that the emotion reaches over :)

Future readiness is being able not to foresee, but adjust fast. Take some bets, be resilient and know FAIL means First Attempt In Learning.

Thank you for sharing.