The Panic That Built WeChat's $700 Billion Super-App

Silicon Valley is selling agents as the next era. But Tencent in Shenzhen had figured it out a decade ago.

马上就做. Do it now.

Four Chinese characters, no meeting invite, and no committee. That was the email reply Allen Zhang received from the CEO.

It was October 2010, and a Canadian startup called Kik had just launched a mobile messaging app. Fifteen days later, it had one million users.

When Allen Zhang found out, it terrified him. He was running a small R&D outpost in Guangzhou, about 90 miles from Tencent’s gleaming headquarters in Shenzhen. Before Tencent acquired Zhang’s company in 2005, he had built Foxmail, a leading email client in China at the time.

Zhang was introverted, even reclusive. He skipped meetings and avoided the limelight. While other executives jockeyed for face time with the CEO, Zhang stayed in Guangzhou and tinkered.

But he understood something that people in Shenzhen didn’t: If nothing changed, Tencent would die.

Tencent had built its empire on QQ, a desktop messaging service with 600 million users. It was the connective tissue of Chinese internet life, sort of like the AOL Instant Messenger of the East.

Heavy with avatars, virtual goods, mini-games, and social layers, it was perfect for internet cafés and dial-up. QQ belonged to that era. And if someone else owned mobile messaging, QQ would become a relic. Tencent would follow.

Zhang’s email to CEO Pony Ma was urgent and unsparing: Mobile messaging posed an existential threat. The company must act immediately.

Pony’s response, 马上就做, didn’t just greenlight Zhang. It set a horse race in motion. There would be one in Shenzhen, one in Chengdu, and Zhang’s small team in Guangzhou.

Three teams in three cities, each with its own philosophy. But only one winner.

Shenzhen pushed the natural evolution: Mobile QQ, the heir to the cash cow. Chengdu built a contacts-first product, betting the address book would become destiny. And in Guangzhou, Zhang would build something new from scratch, without inheriting the weight of Tencent’s past.

The internal tension, people observed, “was as intense as competition with external enemies.”

Why wouldn’t it be? The Chinese internet didn’t do gentle competition. The country did swarms. Talkbox was surging with voice messaging. Xiaomi had MiTalk. And dozens more piled in. Everyone was chasing China’s WhatsApp moment.

Zhang locked ten people into what colleagues sneered was “a little dark room.” They had 70 days. The air smelled of instant noodles, soldered electronics, and nervous ambition. Their budget was a fraction of Shenzhen’s. It didn’t matter. They designed something from scratch for smartphones, not retrofitted from desktop thinking.

On January 21, 2011, Weixin shipped. The world would soon call it WeChat. It did exactly two things: send text messages and share photos.

Within months, WeChat was growing faster than anything Tencent had ever created. And in three years, it would turn a holiday tradition into a financial system.

The Super-App in Your Scan

Two weeks ago, I stood inside Tencent’s Shenzhen headquarters. The head of AI research was explaining how Hunyuan, the company’s AI model, now runs through nearly 900 internal applications, from Tencent Meeting and Weixin to gaming and advertising.

Yes, 900.

The showroom demos felt like a dispatch from a parallel technological universe: fully built, already running. A visitor held up a medicine package. With one scan, WeChat instantly pulled up her medical history, linked her doctor’s appointments, and generated a personalized regime: dosage timing, lifestyle recommendations, and drug interactions.

Far beyond just recognizing the package label, the AI already knew the context of her life. There was no app download and no fumbling with passwords required.

People don’t want more apps. They want fewer interruptions: fewer logins, fewer forms, fewer “now go over there.”

Where does your customer journey still treat the customer like a messenger? They are still copying, pasting, re-entering things that your systems should already know.

“I want a cup of coffee” were the only words that the driver said in another demo. The car, connected to WeChat’s cloud, interfaced with the nearest shop, placed the order, coordinated pickup timing with the navigation route, and handled payment. The car kept moving. When an accident happened elsewhere in the city, routes re-optimized before drivers knew there was anything to worry about.

It went further still.

The subway gate opened with a wave of my palm. There were two cameras, one of which was scanning skin patterns. The other one was reading blood vessels underneath, and it was impossible to spoof. “No more horror movies,” the guide joked, laughing. “Nobody would cut off your hand and use it. You can’t borrow someone’s identity with the dual measurement.” The gate was already in use at Beijing Airport, at 7-Elevens, and at petrol stations across the country.

Next came the meeting software. It tracked speakers across the room, translating Chinese, English, and Dutch at the same time, stripping out background noise as if the room itself had learned how to listen.

Then we stepped into the Mogao Grottoes: life-size, three-dimensional, and fully immersive. You could zoom anywhere. From walls to ceilings, everything projected in VR but rendered in real time, responsive to the smallest movement. These were caves too fragile for public access now. Breath alone could damage them. But here they were again, right in front of me, digitized with such fidelity that you could study paintings more than a thousand years old, and they were close enough that you could see every brushstroke.

Meanwhile, in San Francisco…

OpenAI is racing to build something similar, trying to integrate with Spotify, Booking.com, Target, and Uber. According to The Information, ChatGPT agent—launched last July to complete tasks on users’ computers—fell from four million weekly active users at launch to below one million within months.

Google tried, too. Gemini taps Gmail, Calendar, Google Photos, YouTube, Search, and Maps. It’s clever. But it only works with data that Google already owns.

Standing in Shenzhen, what struck me wasn’t the corporate ambition. It was how ordinary WeChat felt. These weren’t concept demos for a keynote. They were workflows already running. Roughly 1.4 billion people use it every month, with over four million mini programs, more than the Apple App Store or Google Play, and annual transaction volumes comfortably in the trillions of dollars.

Yao Shunyu, Tencent’s high-profile hire from OpenAI, said this: “Even if the model doesn’t get any smarter,” just deploying it better in real-world environments “could generate 10 times or even 100 times the returns.”

In the United States, agents are being trained to navigate the internet. In China, Tencent rewired the internet inside WeChat years ago. It already knows what needs to be navigated. This raised a question that wouldn’t leave me alone.

How did WeChat not just survive the copycat swarm, but outlast Alibaba, outmaneuver ByteDance, and watch American AI giants announce features it shipped years ago?

The answer is a pattern of decisions: panic early, pick a horse, fund it longer than seems rational, and let it quietly become the default.

Principle 1: Let the builder stay where they build best.

The conventional wisdom says that you should consolidate talent, move everyone to headquarters, and optimize for communication and culture. Get your best people in the same room, breathing the same air.

Pony Ma did the opposite.

When Allen Zhang made clear he would not relocate to Shenzhen, would not attend management meetings, and would not conform to corporate expectations, CEO Ma didn’t try to domesticate him. Instead, he established the Tencent Guangzhou Research Institute so that Zhang could stay in his provincial office, tinkering, 90 miles from headquarters. He could skip whatever meetings he wanted.

Call it sentimentality if you want. It was also a talent strategy. Ma trusted that the right person, given the right problem, would find the right solution, even from 90 miles away. So he let them disappear into the work, and he trusted that the work would find its way out.

The same logic that birthed WeChat became Tencent’s gaming playbook: Find extraordinary talent, invest heavily in their IP, and then leave them alone from a distance.

In 2006, a small studio in Los Angeles was building a game called League of Legends. It was unproven and underfunded. Tencent took a 22% stake plus Chinese distribution rights in 2008. By 2011, it owned majority control for between $230 and $400 million. By 2015, it owned 100% of Riot Games.

In 2012, a company in North Carolina was building Fortnite and the Unreal Engine. Tencent invested $330 million for 48%. CEO Tim Sweeney kept control, while Tencent provided global scale. Keep the founder’s hands on the wheel while putting a rocket under the engine.

In 2016, a tiny Helsinki studio with 180 employees was generating $2.3 billion annually. Clash of Clans had become a global phenomenon. Tencent led an $8.6 billion acquisition of Supercell. It was the largest divestment in Finnish corporate history. Supercell’s CEO later explained why he sold to Tencent instead of anyone else: “Their investment secures what has made all of this possible, which is our independence and unique culture.”

Independence was the logic of Tencent. It gave capital plus distribution, without forced “synergy”: just the freedom to let people keep building the way they always had.

The best builders don’t need more check-ins. They need fewer interruptions. Give them clarity, constraints, and cover.

Who on your team would do their best work with less scrutiny and more trust?

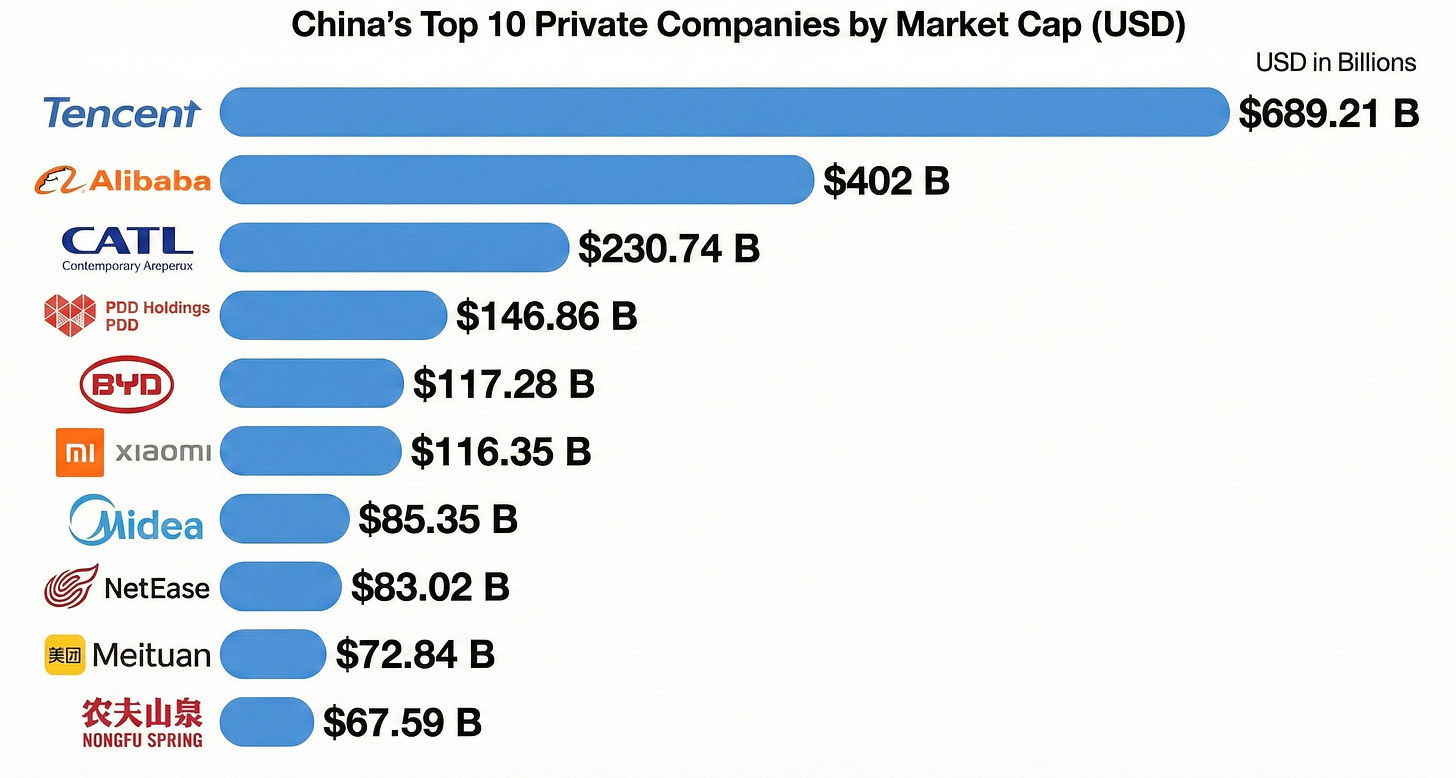

By 2023, Tencent had become the world’s largest gaming company by revenue, bigger than Electronic Arts, Roblox, Nintendo, Xbox, and PlayStation. It generated nearly 28 billion dollars, with stakes in studios across every continent.

This was never a domestic champion that later tried to go global. Internationalism was there from the start: For talent. For acquisitions. And eventually for AI. What I saw in the Shenzhen showroom was fifteen years of borderless strategy, surfaced at last.

If you enjoyed this article and it brought you clarity, could I ask a quick favor? Subscribe now. It’s free and takes just seconds to sign up.

You’ll join 14,000+ other ambitious managers and CEOs receiving exclusive, research-backed insights delivered straight to their inboxes. Let’s keep you one inch ahead.

Principle 2: Ritual first. Revenue later. Defer monetization.

Tencent’s gaming business was printing money. Billions. The board wanted more gaming. Shareholders wanted more gaming. The financially rational move was obvious: Double down on what was working.

Pony Ma ignored them.

He redirected resources to WeChat, which, at the time, was bleeding cash with no clear path to profit. Executives whispered. More than a hundred competitors were chasing the same users. The odds of dominance were slim.

By late 2013, WeChat had defied the odds anyway. Three hundred million users, and growth so fast that it broke Tencent’s own servers more than once. But a new problem kept Ma and Allen Zhang awake at night.

Users were messaging. Laughing. Sharing baby photos at 2 a.m. Meanwhile across town, Alibaba’s Alipay was processing almost every digital transaction in China, powered by its e-commerce business.

Yes, WeChat had the conversations, but Alipay had the money. That imbalance couldn’t last. WeChat needed a way in, and found one in an old tradition.

Every Lunar New Year, cash changes hands in crimson envelopes, moving from elders to children, from bosses to employees, and from friends to friends. Red for luck and prosperity. The custom survived dynasties, revolution, and famine. It would survive digitization, too.

In January 2014, WeChat launched virtual red envelopes.

A grandmother in Beijing opens the app. Her grandson is hundreds of miles away in Shanghai. She taps the screen. A red envelope appears. She types 88 yuan, the lucky number. She hits send. To send and receive the money, she links her bank account. So does her grandson.

That first Lunar New Year, eight million users linked their banks in a single week. Tencent made almost nothing per transfer. Ma wasn’t trying to take a cut; he was still building a new digital habit.

The red envelope wasn’t a “feature.” It was a tradition that already existed. Once the old ritual lived inside the app, payments were no longer a separate battle.

Where’s the red envelope equivalent in your business could you digitize?

Next came another decision that looked like sabotage.

Apple had perfected the walled garden. Thirty percent of every transaction, total control over every app, every developer, and every user. It was the most profitable model in technology history. Tencent had the users now. It had the payment rails. It could have copied the model overnight.

Instead, in 2017, Tencent launched “mini-programs,” sub-applications that lived inside WeChat. No downloads, no accounts, no approval process, and no fees. It was an app inside an app, and anyone could build one for almost nothing.

A bakery owner in a Chengdu alley doesn’t need a developer, an agency, or Apple’s permission. She prints a QR code, tapes it next to the register, and by morning, she has online ordering, loyalty points, delivery tracking, and payments. She has her whole business running inside the same app that her customers use to text their kids.

Tencent was giving away what Apple charged billions for.

James Mitchell, Tencent’s Chief Strategy Officer, explained the following during my visit: “There’s about five million companies in China whose primary online connectivity with consumers is through mini-programs. We believe that’s actually more than companies whose primary connectivity is through standard app stores.”

That is what “ridiculously easy to work with” looks like.

Make it easy for others to build on you. The strongest ecosystems don’t demand loyalty. They earn it by making partners money faster and work simpler.

If a tiny business tried your product tomorrow, where would they get stuck?

Principle 3: Ship capabilities outward so adoption pulls them inward.

This principle came alive during my Tencent visit. “The competitive edge is no longer just the model. It’s the organization’s speed of learning,” Dr. Xiaohui Yuan said, clicking to a slide where a rigid org chart dissolved into a living, evolving network.

Yuan was a senior expert at Tencent Research Institute, and she was describing what she called the two halves of the AI race. “The first half is about the model. They make it more intelligent, improving benchmark scores. The second half is about deployment. They give users easy access to intelligence on demand.”

Then she showed us what collapse looks like in practice. Nearly 900 internal applications now run on their Hunyuan AI model. More than 90% of Tencent’s engineers use their AI coding assistant daily. Half of all new code at the company is now AI-generated.

I wrote the ratio in my notebook. Research, engineering, product. Three silos becoming one.

And Tencent is giving away these tools to external users. Creators can now generate animated videos, 3D models, and content that would have required professional studios just a few years ago. One demonstration showed a user typed a story prompt on screen. Within minutes, it became storyboards. Then animated scenes. Music synced automatically. The quality wasn’t perfect. But it was good enough to post. And it cost her nothing, essentially free.

In Western gaming and media companies, I hear constant anxiety over AI. Artists fear replacement. Engineers resist adoption. Middle managers protect their headcount. Projects stall in committee.

At Tencent, that internal resistance barely exists. Why?

Because they build AI capabilities for external users in parallel. When you’re racing to serve millions of creators outside your company, you iterate faster. You find product-market fit. You build something that actually works rather than something that merely impresses a steering committee. And when internal teams see those external capabilities delivering real value, adoption becomes obvious.

Yuan described what Tencent calls “shadow AI.” Employees secretly buying AI tools on their own, using them without telling anyone. “They don’t want others to know they are using AI tools,” she said. “But the employees at the first line of their business, they know more about user needs.”

So Tencent followed the signal. Top-down investment and bottom-up discovery, happening simultaneously. They didn’t punish the shadow users. They learned from them.

The stuff employees hide from IT is usually the stuff that works. The job is to make the workaround unnecessary by making it official.

What “unauthorized” workaround keeps showing up, and what would it look like to legitimize it?

But now the gaming division has an even more critical mission.

American researcher Fei-Fei Li, often called the godmother of AI, recently argued that spatial intelligence is the next major frontier. She was referring to AI that understands and generates worlds with perceptual, geometric, and physical consistency.

Tencent’s gaming empire matters here. Games are physics simulators disguised as entertainment. They force systems to model movement, collision, lighting, and causality. Every object persistence problem that a game engine solves is a lesson for an AI that will eventually need to understand the real world.

I finally understood why Tencent kept pouring money into games even as the Chinese government cracked down on youth gaming time. It wasn’t building entertainment; this is the training grounds for spatial intelligence. Tencent just called them Honor of Kings and PUBG Mobile.

“You can imagine,” Yuan said, “if this technique can be combined with the physical world, then we can let robots test in simulated environments. It can lower the cost a lot.” She paused. “If we can bridge the gap between digital intelligence and physical actuation, robotics, autonomous driving, it’s a very great potential.”

In the West, AI is often framed as a cost-reduction story: Automate support tickets, draft emails, and reduce headcount. The ROI is measurable. And it’s usually uninspiring.

Tencent is playing a different game: AI as capability expansion, for internal teams and external creators alike.

In fast markets, “best” rarely wins. “Used” wins. A slightly weaker tool in millions of hands will outrun a brilliant tool trapped in pilots.

Where are you optimizing for “impressive” instead of “used every day”?

And Tencent isn’t hoarding capabilities. Chinese AI models now represent 36% of publicly released large language models globally. In just one year, Chinese open-source models surged from a 1.2% rounding error in late 2024 to more than 30% of global usage. One Silicon Valley venture capital firm told me that 80% of the startups they review are building on Chinese AI models.

These models are good, they're open, and they cost almost nothing.

A Cheap Tech Giant

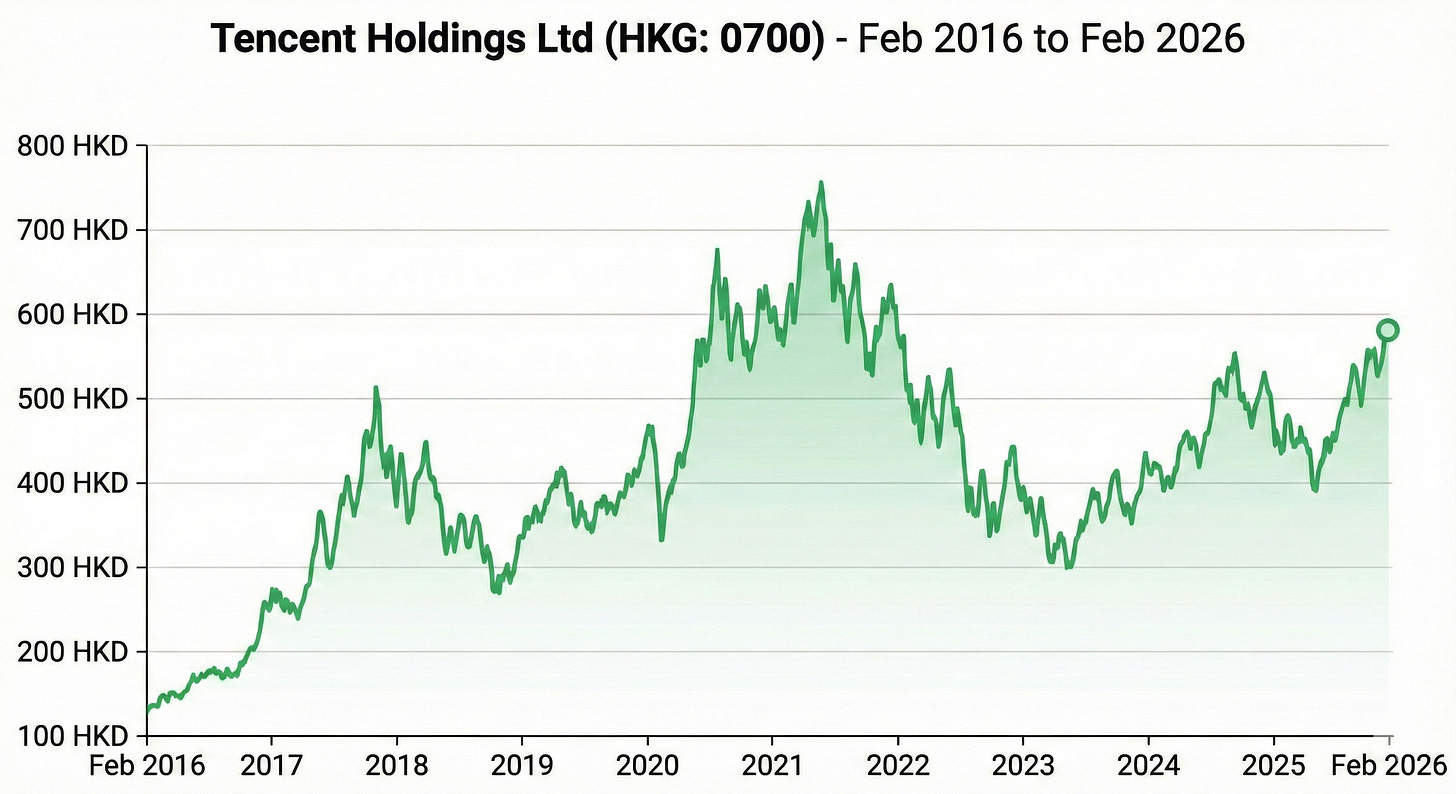

Tencent’s market capitalization sits just shy of $700 billion. That’s less than one-fifth of Google’s parent company, despite comparable user scale and deeper ecosystem integration. Chinese tech valuations have been suppressed by geopolitical tensions and regulatory uncertainty.

But Pony Ma doesn’t seem to care. Neither does his management team. If anything, the discount has freed Tencent from the pressure to maximize quarterly numbers. They can build for decades instead.

And so the technology trajectories continue to diverge. The United States optimizes for benchmark performance. China, in contrast, optimizes for practical value at scale.

And chip restrictions may have accelerated this even further. If Chinese firms can’t count on the best hardware, they learn to make models that run lean and fast, which is exactly what you need for cars, robots, and edge devices where latency is fatal.

Western companies can’t copy Tencent, and shouldn’t try. What works in Shenzhen won’t transplant to San Francisco. Context matters.

But the underlying principles translate.

Build your second engine while your first is still roaring. Make yourself so easy to work with. Defer monetization. Deploy new capabilities externally and internally at once. Open your ecosystem so completely that you become the ingredient everyone else builds on.

Time horizon is a weapon. Many teams lose because they optimize for the next quarter while someone else optimizes for the next decade.

What would you build differently if you were allowed to think in 5 years instead of 5 weeks?

We don’t need to agree with China’s approach to technology to recognize what’s happening. The next generation of spatial intelligence, contextual AI, and embedded machine learning is being built right now.

Some of it is in Silicon Valley. But much of it is in Shenzhen.

This is a great article! I still remember when the red packet feature came out, I happened to be in Beijing at the time, definitely a FOMO moment where everyone rushed to link their bank accounts to wechat 😆. I love how you drew out the learning principles, particularly refreshing is the idea of how ritual/tradition can play such a significant role in product offering. Great food for thought👍

👍❤️ 韬光养晦,壮志华夏。There is so much Vision and Self-restraint displayed by Tencent.

Thank you for the article. It's an eye-opener.

( I've been a long time reader of yours, really appreciate your generous sharing + 独到见解. )