The One Chart That Explains Everything

And the seven books that make sense of America's AI Anxiety and China's AI Optimism

If one chart captures the global mood as the holidays arrive, it isn’t a stock index, an inflation line, or a defense budget.

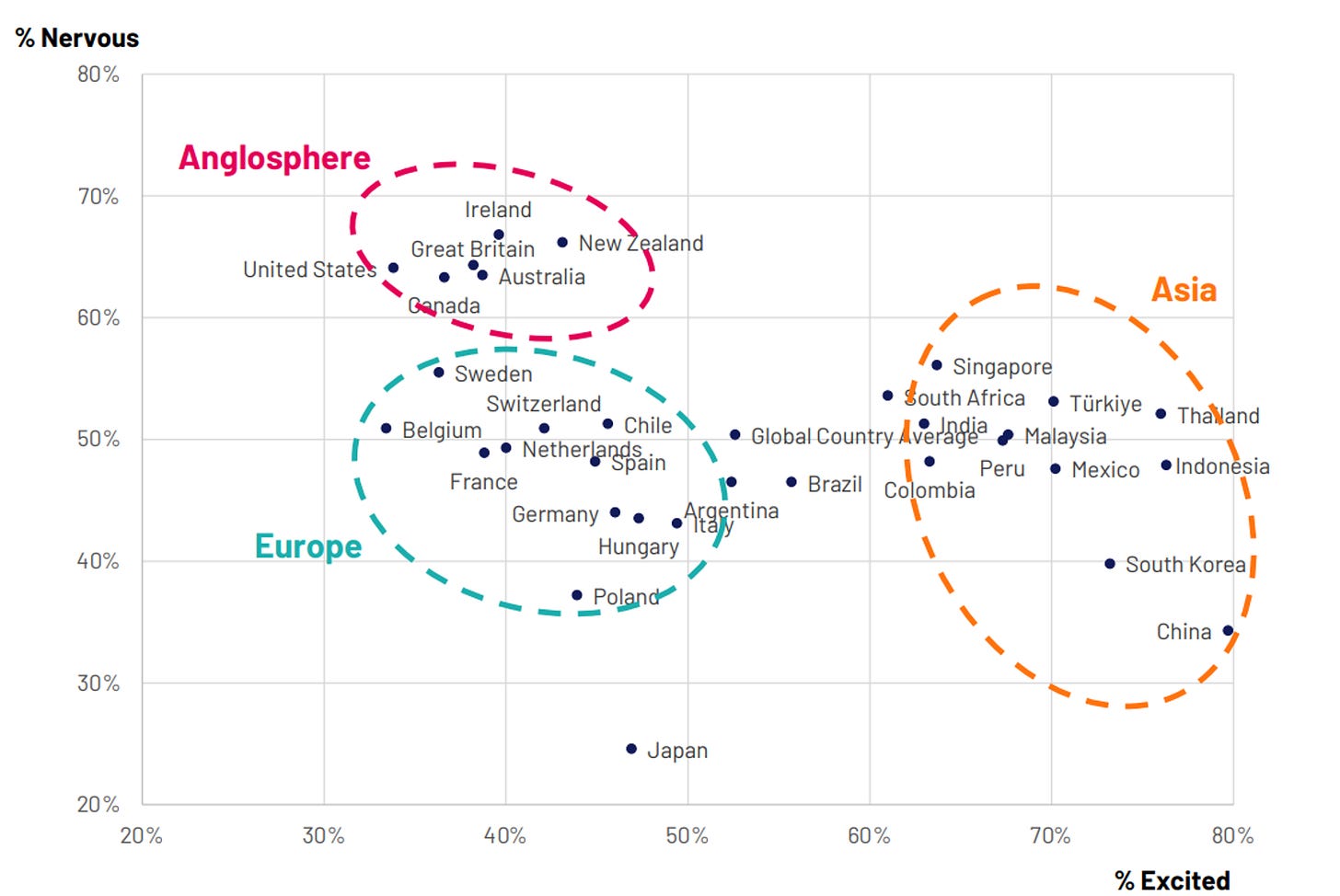

Here is a scatter plot mapping the world’s emotional response to artificial intelligence.

On the X-axis, you have excitement; on the Y-axis, nervousness. The world splits into two distinct clusters.

You have the United States and much of Western Europe in one cluster: wary, anxious, bracing for impact. In the other, China and its Asian neighbors: optimistic, eager, racing to adopt.

This divergence made no sense to me for the longest time. Why would the United States, birthplace of the silicon chip and home of OpenAI, Google, and the modern internet, be the most terrified of its own creation?

Why would China, a nation the West sees as rigidly controlled, be the most buoyant amid technological chaos?

I couldn’t understand it until I started reading.

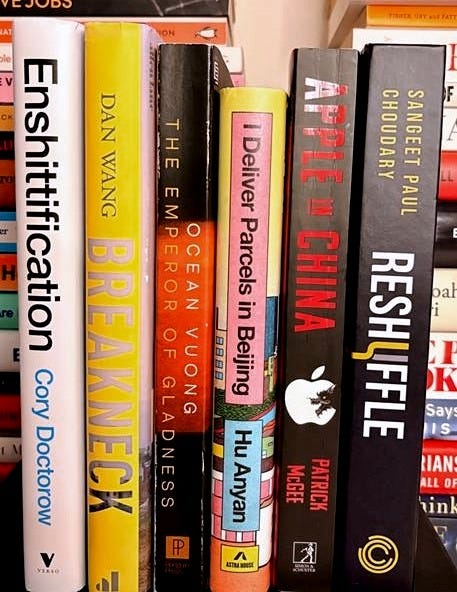

Seven books I binged this year finally gave me the answer. They took me from factory floors in Shenzhen to a designer’s desk in Spain, from an Amazon merchant lost in the maze to a Beijing delivery driver chasing hope. In their lives, I saw what the scatter plot never could: two worlds, the same technology, and utterly opposite dreams.

The answer has nothing to do with benchmarks, parameters, or whether the next model hallucinates less. What matters are the stories societies tell themselves about work, worth, and who gets to win.

When people answer the question, “How do you feel about AI?”, they aren’t talking about software.

They are asking: when this wave hits, who does it lift?

Progress and its Discontents

History reminds us that progress is not automatic, and it certainly does not trickle down.

MIT economists and Nobel laureates Daron Acemoglu and Simon Johnson comb through a thousand years of technological change in their book Power and Progress.

The conclusion they reach is unforgiving: most innovation has made a small group of people fabulously rich, while leaving everyone else behind.

In medieval Europe, better plows boosted harvests. Lords got richer; peasants did not. During the early Industrial Revolution, textile machines transformed productivity. Factory owners built estates; workers died in slums.

There is one glaring exception: the mid-20th century. But shared prosperity wasn’t the natural outcome. It was fought for with unions, strikes, and policy battles.

That brings us to today. Each new AI tool promises efficiency while erasing the bottom rung of the career ladder. No junior analysts, no first-year associates, no training ground at all. Gen Z may be wrong about the details, but they are right about the feeling. The game feels rigged.

Acemoglu and Johnson throw in one hopeful example. In the 1970s, ATMs arrived, and everyone predicted the death of the bank teller. The opposite happened: teller numbers grew. Why? Because machines took over the dull work, like counting cash, and freed tellers to become financial advisors, relationship builders, and problem solvers. The job got better.

Then there’s the other path.

I thought about this last autumn, standing in an Amazon Go store. The technology was flawless. Cameras tracked my move. Algorithms calculated my bill. No lines, no cashiers, no friction, and also no people. Just me, alone, in a perfectly optimized box.

Acemoglu and Johnson call this “so-so automation.”

Technology that displaces workers without meaningfully improving anyone’s life.

It’s capital-intensive, soul-crushing, and highly profitable.

Here’s the choice. One path treats technology as human augmentation. The other treats it as profit extraction. The trend is unmistakable. Since the 1980s, America’s top 10% have pulled sharply away from the median. For low-income men, real earnings have fallen, with lower pay and fewer hours worked.

That’s why when Americans look at AI, they aren’t asking, “What can this technology do?” They are asking, “Who’s going to rob me this time?”

When Tech Breaks Trust

In 2014, a barber from Michigan named Douglas Mrdeza started selling surplus hair products on Amazon. His first offering, a specialized pomade, sold out. So he kept going. The fees were reasonable: about 19 cents on every dollar. He was grateful for the traffic.

By 2017, Amazon’s cut had climbed to 26%; by 2018, 30%. Mrdeza didn’t panic. He hired forty employees, many of them people still looking for work after the Great Recession, and leased four warehouses. His company, Top Shelf Brands, hit $25 million in annual revenue and landed on Inc. Magazine’s list of America’s fastest-growing private companies. “It was like living the dream,” he later recalled. “We were all in.”

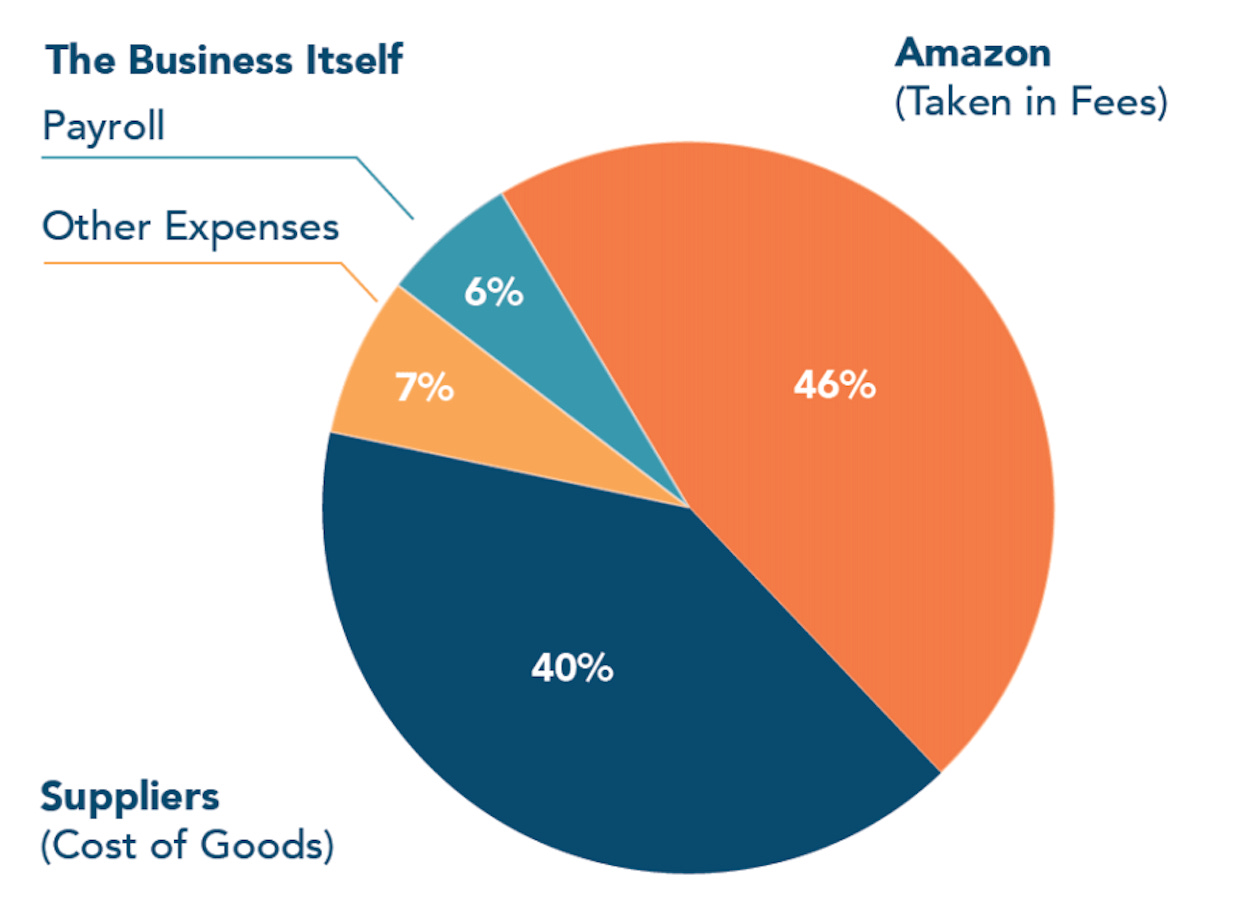

Then he opened his seller dashboard and did the math. Amazon was now taking 46 cents of every dollar he earned. After paying suppliers, only 13 cents remained to cover employees, rent, insurance, and everything else. Top Shelf Brands was bleeding red.

By 2019, Mrdeza was forced to fire all but five of his employees. By 2022, Top Shelf Brands filed for bankruptcy, and he let go of the rest. “If you actually add up all the ways Amazon nickels and dimes you,” he said, "you can’t make money."

But here is what makes my jaw drop.

Mrdeza tried expanding to eBay and building his own website, but he couldn’t escape by selling cheaper elsewhere. Amazon forbade it. Amazon monitored off-platform prices algorithmically. Sell a bottle of shampoo for one dollar less on Walmart.com or on your own site, and Amazon retaliated. Your search ranking tanked. Your “Buy Box” vanished. Your product became undiscoverable.

This is the playbook Cory Doctorow calls Enshittification.

Seduce: Be generous. Subsidize users. (In 2014, Amazon took only 19%.)

Lock-in: Become essential. Make leaving painful.

Squeeze: Raise fees, degrade service, extract rent.

Defend: Build moats so high that competition dies in the desert.

Amazon ran this playbook. So did Facebook. “Trust us with your data.” Then came the micro-targeting. “Trust us with your news.” Then came the rage-bait algorithms. “Trust us with your attention.” Then came the infinite scroll, engineered by the same psychology that designs slot machines.

We know the platform is degrading. We know the ads are multiplying. And yet, “we can’t leave,” Doctorow admits. Our friends are there. Our customers are there. Our photos, our history, our identity.

I’m not here to call Amazon evil. Maybe this is just efficient capitalism doing its job. But when people watch enough scrappy startups transform into rent-seeking empires, trust erodes.

Once trust collapses, every innovation arrives pre-loaded with suspicion.

Every “We’re here to help” sounds like a con.

So, when AI arrives—the most powerful technology since electricity—the average American doesn’t feel wonder. They think, “Here we go again.”

The Coming Unbundling

By now, the dread had set in. Still, I didn’t grasp how trapped even the tech giants feel until I cracked open Sangeet Paul Choudary’s Reshuffle.

Choudary’s core idea is deceptively simple: AI isn’t just a faster tool or a smarter assistant. You should think of it like a solvent. It dissolves the glue that holds companies together. His most unsettling case is Shein, the Chinese fast-fashion company that seemed to materialize out of thin air.

Here’s what Shein does. Forget the old model: designers sketching collections in a loft, buyers flying to Milan, warehouses stuffed with unsold inventory.

Instead, Shein monitors real-time search data and TikTok feeds to spot micro-trends the moment they pop up. Then it fragments the work among thousands of small suppliers who crank out clothing in batches of fifty, sometimes twenty. An AI-driven system orchestrates who makes what, routing orders like air traffic control. The right designs hit Shein’s app at lightning speed. Popular items get reordered within days. The flops vanish.

The result? A $66 billion company built overnight.

According to a recent survey, 64% of professionals feel overwhelmed by how quickly work is changing, and 68% are looking for more support to keep up. If you enjoyed this article and it brought you clarity, could I ask a quick favor?

Subscribe now. It’s free and takes just seconds to sign up.

You’ll join tens of thousands of other ambitious managers and CEOs receiving exclusive, research-backed insights delivered straight to their inboxes. Let’s keep you one inch ahead.

From a business perspective, it’s terrifyingly brilliant. If brands like Zara, H&M, Adidas, and Nike want a future, they’ll have to imitate parts of Shein’s playbook.

But what happens to the people who used to hold those jobs? The fashion buyers, the merchandisers, the retail planners, even the designers.

In Shein’s model, expertise is splintered across a network so diffuse that no single worker is vital. The system doesn’t make designers more productive, the role of “designer” has been rendered irrelevant.

A job used to be a whole, but AI turns it into tasks.

Tasks get routed. Routed work gets commoditized.

Choudary warns this is the future of knowledge work. AI breaks a job that once belonged to one person into a hundred tasks, coordinated by an algorithm. The spoils go to the platform owners. The professionals? The knowledge workers? They become interchangeable parts. That includes coders at Google, scientists at Pfizer, and even (God forbid!) professors at business schools.

“The value of higher productivity hasn’t flowed to the workers,” Choudary writes. “It is captured almost entirely by aggregators.”

If you’re the CEO of a Fortune 500 company, you have no choice but to embrace this “reshuffle,” even if it means gutting your own organization before someone else does. Refuse, and your board will find another CEO who is willing to make the change.

I closed the book and just sat there for a while. If you’re feeling vertigo at this point, you’re not alone.

What happens to the people left behind?

The Teenager Who Almost Jumped

“Fiction reveals truth that reality obscures.” In The Emperor of Gladness, Ocean Vuong takes us to a decaying New England town to meet Hai.

Hai is nineteen. A college dropout and recovering addict, he spends his days wiping down tables at a Boston Market-style restaurant, the smell of artificial gravy clinging to his skin. One summer evening, he stands on the edge of a bridge. He is ready to jump.

He’s trapped in a place with no jobs, no prospects, no way out. He lies to his mother that he’s going away to college because the truth, that he’s ladling gravy for minimum wage, would break her heart. He’s stuck in the “low-wage service sector,” the very sector economists cheerfully tell us is the future of American employment.

Fear is what happens when you stop believing society will catch you.

Hai is saved. Not by a government program, not by a tech startup, and certainly not by AI. He’s saved by Grazina, an 82-year-old widow with dementia.

An accidental bond forms between these two lonely souls discarded by the “efficient” market. He becomes her caretaker. In washing Grazina’s soiled clothes, listening to her fragmented memories of Lithuania, and holding her fragile hand as she falls asleep, Hai finds a reason to exist.

He finds redemption, but he does not find economic progress. This is the tragedy haunting the American scatter plot. For a huge segment of the population, dignity is now divorced from the economy. Hai finds meaning, but he is still poor, still stuck, no matter how hard he tries.

Vuong leaves us with a lingering question: is a society successful if it creates trillion-dollar companies but leaves its children so hopeless they want to die in a Boston Market parking lot?

And if this is the emotional baseline of the Anglosphere—progress without protection, innovation without trust—then nervousness on that chart makes perfect sense.

Now, spin the globe. If you look across the Pacific, the mood shifts instantly. Why is China so excited?

The Engineering State

Let’s stop asking, “Who has the best AI?” and instead we’ll ask, “Where does progress feel visible?”

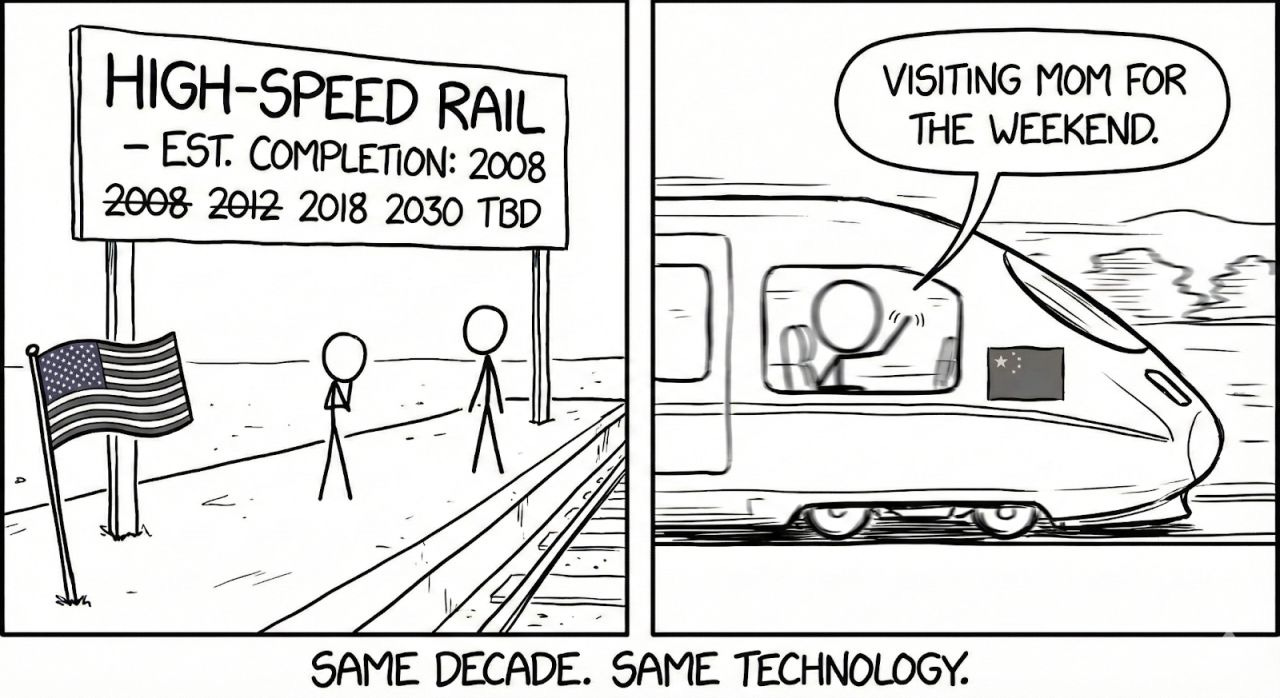

Dan Wang’s book Breakneck argues that China behaves like an Engineering State—relentlessly building—while the U.S. behaves like a Lawyer Society—endlessly debating. Whether you agree or not, it’s a powerful lens.

In 2008, California approved a bullet train from Los Angeles to San Francisco. That same year, China broke ground on the Beijing–Shanghai high-speed railway.

Sixteen years later, California’s train is still trapped in lawsuits and environmental reviews. Not a single passenger has boarded. China’s line was finished in three years. Today, it moves millions of people a day at 217 mph between the nation’s two biggest cities.

While California argued over paperwork, China poured concrete.

Bridges in Guizhou turn four-hour drives into twenty-minute glides. Power lines drag wind energy from Xinjiang to Shenzhen.

The smog in Beijing, once gray and choking, has cleared thanks to an aggressive shift to EVs and nuclear power.

For the average Chinese citizen, “technology” is the reason they can visit their parents for the weekend. It’s the reason they can book a doctor on WeChat in seconds. The excitement on that survey chart comes from this tangible reality. Progress is concrete. It’s steel; it’s speed. You can see it, touch it, ride it. It breeds a public expectation that the future is being built, and I’ll get a piece of it, even if I’m not one of the elites.

But how did China get so good so fast? Apple in China by Patrick McGee reveals an irony: American capitalism taught them how.

For decades, U.S. companies outsourced to China to cut costs. Apple was the master. Through ruthless demands and on-site engineering, Apple trained a generation of Chinese factories to meet impossible standards. Think of the unibody aluminum MacBook. The unbreakable Gorilla Glass. Those seams so perfect you can glide a fingernail across and feel nothing. Apple became a trillion-dollar company on the back of Chinese suppliers, achieving cost structures and margins it could only dream of if it kept manufacturing in California.

Those capabilities didn’t stay locked inside Apple. Once a supplier can build the impossible for Tim Cook, building for everyone else is easy. Huawei, Xiaomi, Oppo, Vivo: China is simply turning that hard-won manufacturing wizardry into world-class smartphones and gadgets of their own.

Then came Tesla. Elon Musk built the Shanghai Gigafactory in under a year, from muddy field to rolling cars. Tesla singlehandedly provided a template for speed and scale that local EV makers gawked at. Before long, companies like BYD, Xpeng, and Li Auto were cranking out competitive electric cars, powered by that shared knowledge of how to get things done fast.

China’s optimism is largely a lived experience.

It is waking up to new skylines, new trains and bridges, and new gadgets in your hand.

The Courier’s Reality

But this isn’t a utopia. I Deliver Parcels in Beijing by Hu Anyan brings us back down to earth.

Hu is the Chinese counterpart to Ocean Vuong’s Hai. He is a gig worker, a courier in the relentless machine of Chinese e-commerce. His story is a catalog of humiliations: arbitrary fines from the delivery app, brutal 14-hour days, customers who treat him like he’s invisible.

He writes about the “algorithms of control.” The app barks orders, telling him which alley to turn down, exactly how many seconds to make the drop. If he’s 60 seconds late (ping!), money is deducted from his account. It is the “Shein-ification” of logistics.

And yet... there is a difference. Unlike Hai, who feels trapped in a dead end, Hu feels like part of a rising tide. There is a frenetic energy to his struggle. He has worked 19 different jobs across six cities over two decades. He’s always hustling, always convinced that there’s an angle to work, a ladder to climb. Shenzhen burns you out? Try your luck in Chengdu. Didn’t find your fortune in e-commerce? Maybe a solar panel factory boomtown will suit you better.

It’s a brutal sort of optimism, perhaps, but it is optimism, nonetheless. Hu is suffering, but he’s suffering in a system that’s moving.

Crucially, the Chinese state isn’t shy about cracking the whip on the winners. In China, nothing is too big to rein in, nothing too big to jail. Remember when Alibaba’s finance arm, Ant Group, was about to launch the biggest IPO in history?

The government slammed on the brakes, effectively saying, “Not so fast.“ Jack Ma, once China’s most flamboyant billionaire, disappeared from public view. The message didn’t need explaining: no tech company stands above the state. If a trillion-dollar company starts to threaten shared prosperity, it can be cut down to size.

For many Chinese people who came from the countryside to work in the megacities, that was reassuring.

No corporation is invincible. No CEO is untouchable.

Once I saw all this, that original U.S.–China AI attitude chart stopped being a mystery. When people feel like their society is on an upward trajectory, they welcome an accelerant like AI. When people feel stuck or cheated, they fear the shake-up.

This isn’t an argument for China’s system. But it does explain how different systems make people feel about the future.

The Referendum on Feeling Invited

When I look back at the year through these seven books, I stop thinking about technological rivalry. Beneath it all, something far more consequential is at stake: a rivalry of social contracts.

In one social contract, call it the American one, people assume progress will be captured by a few, while everyone else is told to “reskill” on their own dime and do it fast, on a runway that is already on fire.

In the U.S., too many people open the same apps and reach the same conclusion: we are being monetized. They have seen this movie before. They know who gets rich in the end.

In the other social contract, the Chinese may not enjoy Western-style political freedoms, but they do see a state that can still build for the masses, one that is willing to yank the leash when private power runs too far ahead.

There is a lived belief that the gains of progress might reach regular people, or at least that the government will not let tycoons run completely amok.

That difference, the belief about who captures the value of progress, shows up as fear or excitement long before anyone fully understands a new technology. It’s a referendum on whether people feel invited into the future or not.

So, if you’re a business leader reading this, let’s not just ask “How do we adopt AI faster?” We must also consider, “How do we deploy AI in a way that makes people believe the future includes them?”

Because no one can market their way out of deep distrust.

I was reading this and thinking that the Anglophone mindset goes back further to the rise of a very narrow definition of shareholder value fostered by the likes of former GE CEO Jack Welch and financiers influenced by the Chicago School of Economics and UK financiers like Sir James Goldsmith, Jim Slater and Peter Walker.

They broke the back of organised labour, broke the mid-century social contracts between labour and capital and atomised tasks along a global supply chain.

Technology is seen to be following in their path. Three generations of workers in the Anglophone countries have seen this in action so trust is very unlikely to be rebuilt. The refuge back then was the rise of the 'knowledge worker', but now capital and LLMs are coming for that too.

This is why you have the rise of the far right and the far left in your countries on the lefthand side of the chart.

The countries dominated by the American style capitalist economic values operate with an extractive, exploitive ("plunder, rape, milk at all costs") frame of mind. And its spread throughout the world is pervasive. Each of one us do have to think and choose what type of society we want to build in the countries we live in: one where technological advancement benefits all residents (tech for greater good) or one where technological advancement is a weapon used by individuals to pit against each other for personal gain.