The Automation Fork in the Road: Where Does Your AI Path Lead?

If an AI plan demoralizes the people required to make it work, then it’s not automation. It’s erosion.

In 1982, General Motors shuttered its assembly plant in Fremont, California. That plant was the worst of American auto. Relations between management and the United Auto Workers were poisonously adversarial. Absenteeism hovered around 20 percent. Workers drank on the job, filed endless grievances, and even sabotaged the cars they were building. The quality of the vehicles that rolled off the line was the worst in GM’s system.

Two years later, the same plant reopened under a new name: New United Motor Manufacturing, Inc. (NUMMI). This time, it was run by Toyota. And Toyota rehired the very same workers GM had employed. It used the same people, the same union, and the same building as GM.

Within a year, the Fremont plant became one of the most productive and highest-quality factories in America. Absenteeism dropped to 2 percent. Grievances virtually disappeared.

What changed? Workers got the andon cord, which was a rope that anyone could pull to stop the entire production line if they spotted a problem. At GM, stopping the line was forbidden. At Toyota, it was encouraged. Pulling the cord was not failure: It was improvement in action.

The Rope That Saved a Factory

The NUMMI miracle proved that the workers were never the problem. It was the system, which had disempowered people by treating them as cogs in a machine. Toyota succeeded by building a socio-technical system where technology was designed to augment human workers, not replace them.

Robots took care of dangerous and repetitive tasks. Humans handled complex judgment, and continuous improvement. Workers became problem-solvers, not cogs. Automation served people and not the other way around.

Because human dignity drove business performance.

The Fork in the Road: Who Gets the Gains?

I tell you this story because we are living through our own revolution. The prevailing narrative around AI is one of inevitability. We tell ourselves that a tidal wave of automation is arrive. Our only choice is to embrace it or be swept away.

Not only is this sense of techno-determinism disempowering, it is also wrong.

History shows that certain innovations lift all boats, creating new jobs and higher living standards, while others enrich a few at the expense of the many.

In medieval Europe, the spread of watermills and windmills dramatically increased agricultural productivity. Yet the wealth they generated flowed mostly to the church and aristocracy. They financed cathedrals and castles. Meanwhile, peasants continued to live in squalor.

During the first century of Britain’s Industrial Revolution, immense fortunes were made by industrialists. However, the real wages of the working class stagnated for decades. Only when we directed technology after WWII—pairing new tools with education, bargaining power, and public goods—did advances in medicine, aviation, home appliances, and IT translate into broad prosperity.

As MIT economist and 2024 Nobel laureate Daron Acemoglu argues in Power and Progress, the trajectory of technology is not a force of nature but a matter of choice. “Progress is not automatic,” he writes, “but depends on the choices we make about technology.”

The crucial insight here is that the impact of automation on employees is also not preordained. Instead, it depends entirely on the choices that business executives make about the kind of automation that a company develops and deploys. At the corporate level, this creates a fork in the road—one that shapes not only the future of employees but also the very nature of a business itself.

The 2×2 That Matters

Now, I am not a sociologist or a macroeconomist. I am a strategy professor at a business school. Therefore, I will stay in my swim lane with a 2x2, even when discussing a general-purpose technology like AI.

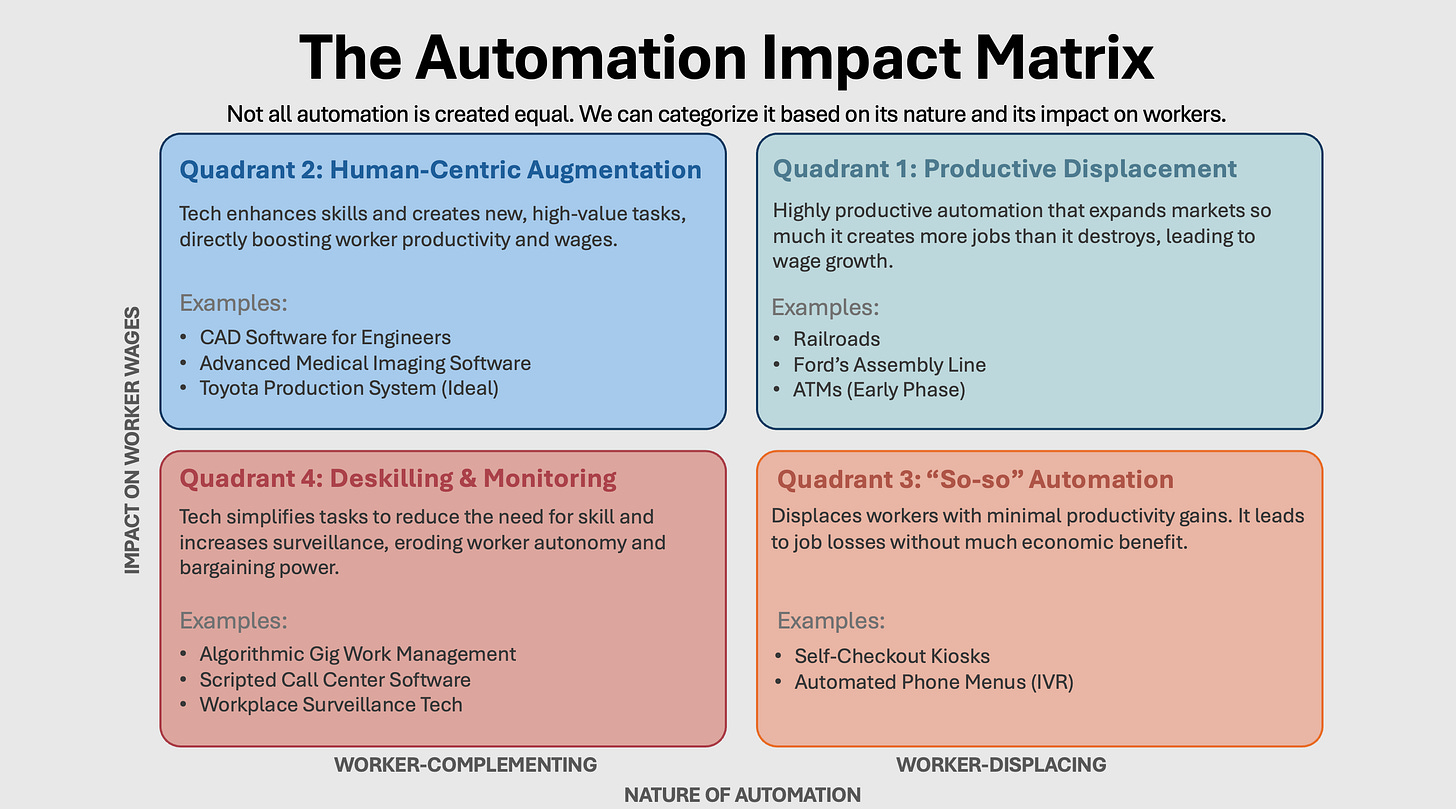

This matrix sorts technology based on two questions: 1) Does it work with people (complementing) or instead of them (displacing)? 2) Does it make their work more valuable (raising wages) or less (stagnant or falling wages)?

The four quadrants that result—Augmentation, Productive Displacement, So-So Automation, and Deskilling—map the choices that every company is making.

Let’s dig into some real-world examples from these categories to understand why they sometimes fail and how we can do better.

The Clean‑Swap Mirage (So‑So Automation)

We’ll start with the trap of “so-so” automation, the bottom-right corner of the matrix. Its allure lies in seductive simplicity, promising a clean, technological fix for the messy, human-centered challenges of business: labor costs, inefficiency, and human error. This form of automation offers the vision of a frictionless world, where operations hum with the quiet perfection of an algorithm.

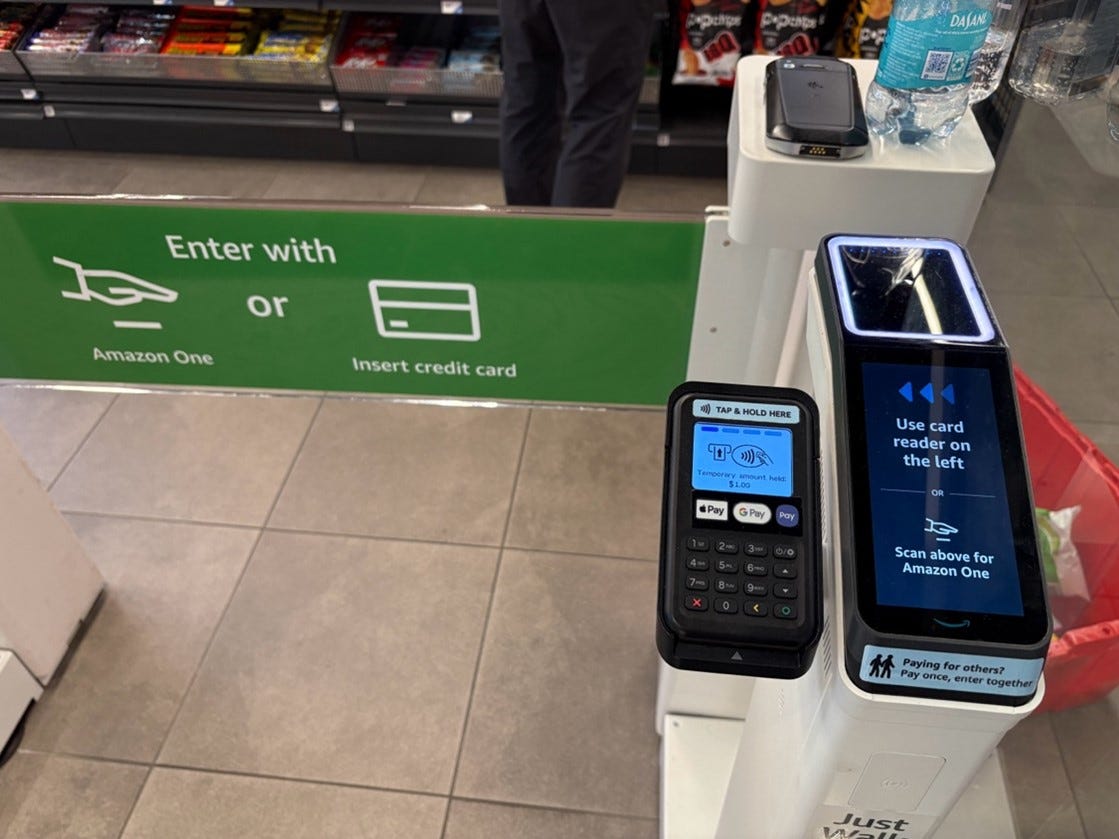

This was epitomized by Amazon Go, which launched in 2018 with dreams of opening 3,000 cashierless stores. At its peak by 2023, only 30 of these stores existed. By 2025, half of them had already closed. The “Just Walk Out” technology, with its cameras, sensors, and AI, had promised frictionless shopping but delivered only marginal gains.

Field Note: Newark’s Cashierless Kiosk

I experienced Amazon’s experiment firsthand at Newark Airport in New Jersey. At the terminal, I spotted an Amazon Go kiosk and decided to try it. My Apple Pay unlocked the entrance with a digital beep. Inside, shelves were neatly stocked, overseen by one employee who was restocking and pointedly avoiding eye contact. I grabbed a sandwich and walked out. The turnstile registered my departure and charged my card.

A traveler behind me asked, “Is that it?” Then, under her breath, she said, “We need to humanize this place.”

Even when everything worked flawlessly, the store felt eerily sterile. It was more like a vending machine than a shopping experience. One passerby peeked inside, saw no cashier, and walked away, unsure how to begin.

Friction left, and trust left with it.

Viewed through Acemoglu’s lens, Amazon Go is the quintessential case of “so-so” automation. It displaced cashiers but at exorbitant capital cost and with significant operational trade-offs. It was a dazzling technological solution to a low-value business problem.

Ultimately, it suffered from high capex, low empathy, and minimal business upside.

The same pattern occurred at Tesla. Elon Musk once declared that the Model 3 factory would be an “alien dreadnought” of automation. He claimed that it would automate even the fiddly tasks still performed by humans at other carmakers: threading wires, aligning trim, and precision fitting.

Tesla filled the line with robots for parts conveyance and module assembly. The result was chaos: clogged lines, frequent breakdowns, and monumental delays.

Musk eventually ripped out much of the automation and brought back human workers just to get production moving. Later, in a moment of candor, he made the following admission: “Excessive automation at Tesla was a mistake… Humans are underrated.”

What’s the lesson here? Just because you can automate something doesn’t mean you should.

When Tech Deskills and Demoralizes

Worse than so-so automation is when technology actively degrades job quality and exploits labor: Quadrant 4.

Here, the concern is not that a project will fail. In fact, it will succeed in a narrow sense. But that success comes at a steep human price. In the long run, this, too, is a failing strategy, because a demoralized and devalued workforce does not innovate.

According to a recent survey, 64% of professionals feel overwhelmed by how quickly work is changing, and 68% are looking for more support to keep up. If you enjoyed this article and it brought you clarity, could I ask a quick favor?

Subscribe now. It’s free and takes just seconds to sign up.

You’ll join thousands of other ambitious managers and CEOs receiving exclusive, research-backed insights delivered straight to their inboxes. Let’s keep you one inch ahead.

To understand the stakes, look at an extreme case: Foxconn. In the 2010s, Foxconn was Apple’s primary manufacturing partner, assembling iPhones by the millions in massive Chinese factories. This wasn’t a case of robots replacing workers. Rather, Foxconn modernized assembly lines with a Quadrant 4 approach to labor.

The production process was broken into ultra-specialized, repetitive tasks, with technology guiding the pace and monitoring output. Thousands of young workers lived in on-site dorms, waking up to stand on production lines performing the same motion every few seconds, 12 hours a day. Supervisors used electronic scoreboards and CCTV to enforce quotas.

Then a spate of worker suicides at Foxconn’s Shenzhen “iPhone City” made international headlines. Among these cases, there was one that stood out: A 17-year-old girl, Tian Yu, threw herself from her dormitory window after just a month at the plant.

Coming from a rural village, she had arrived full of hope and was lured by promises in the recruitment brochure: “Your dreams extend from here to tomorrow.” Instead, she was thrust into a digital-age assembly line that treated her as a cog in a machine.

Her job was to polish iPhone screens: seventeen hundred a day. She worked under constant surveillance, where she was publicly scolded for the smallest mistake and forced to write self-criticisms. Her first month’s wages were withheld entirely due to an “administrative error.” Exhausted, isolated, and hopeless, she attempted suicide. She survived but was left paralyzed from the waist down.

Even outside factories, the encroachment of surveillance tech is the warning sign of Quadrant 4.

The Human Cost Has a Business Cost

In white-collar offices, “bossware” monitors keystrokes and webcam activity, scoring employees on how “active” they appear. In warehouses and call centers, every motion and word is analyzed. The stated goal is efficiency. But when every bathroom break is timed, workers feel dehumanized. Eventually, this breeds distrust and disengagement.

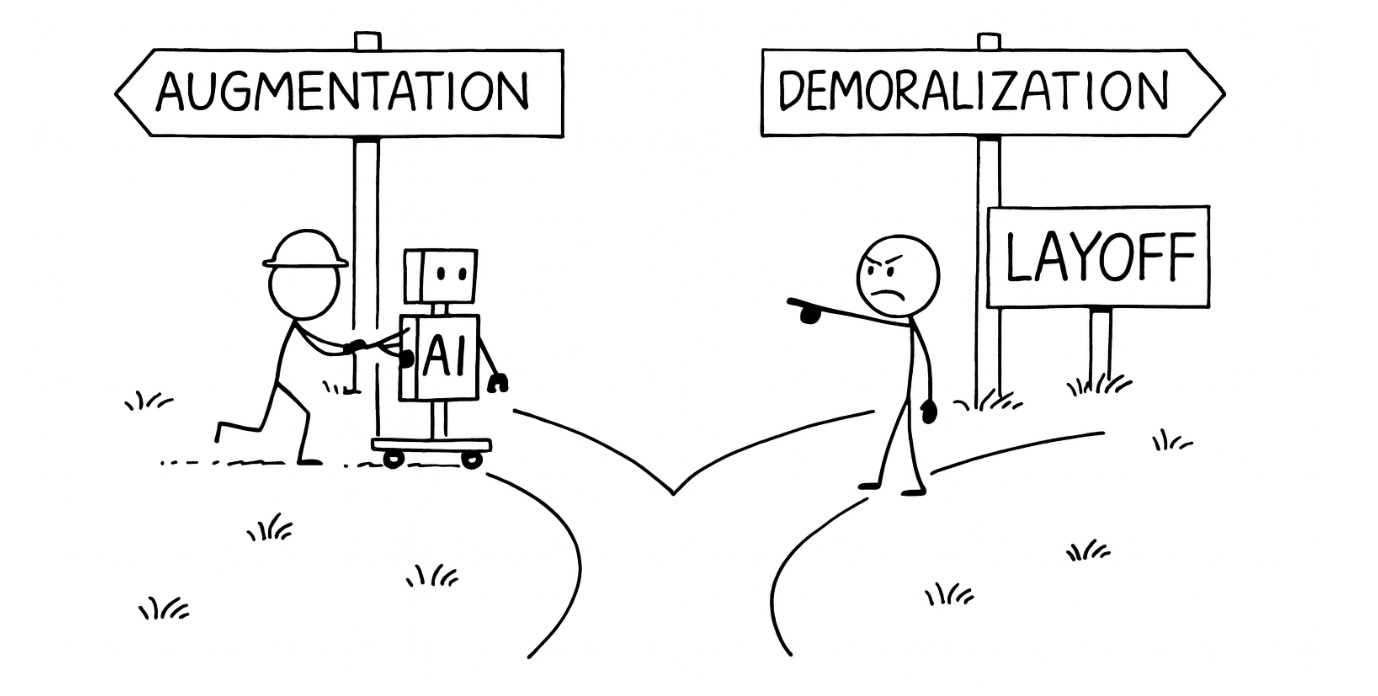

This is not an argument against technology. Rather, it’s an argument against how technology is chosen and used, because it doesn’t have to be this way. With AI, we face a fork in the road.

Down one path is demoralization. Down the other are Quadrants 1 and 2 in augmentation, new role creation, and human-centered design.

The better path doesn’t appear by accident. It requires courage and imagination.

Let’s explore what that looks like and how several forward-thinking organizations are already pioneering it. Automation isn’t destiny; it’s direction. Leaders choose the quadrant.

Augmentation: Where Humans Get More Valuable

The success of Toyota’s NUMMI plant finds its theoretical grounding in the work of another MIT economist, David Autor. His foundational insight is that automation rarely eliminates jobs wholesale. Instead, it eliminates specific tasks within those jobs.

This distinction is critical. When technology automates routine tasks, it does not necessarily make the human worker obsolete. Instead, it increases the economic value of their remaining non-routine task.

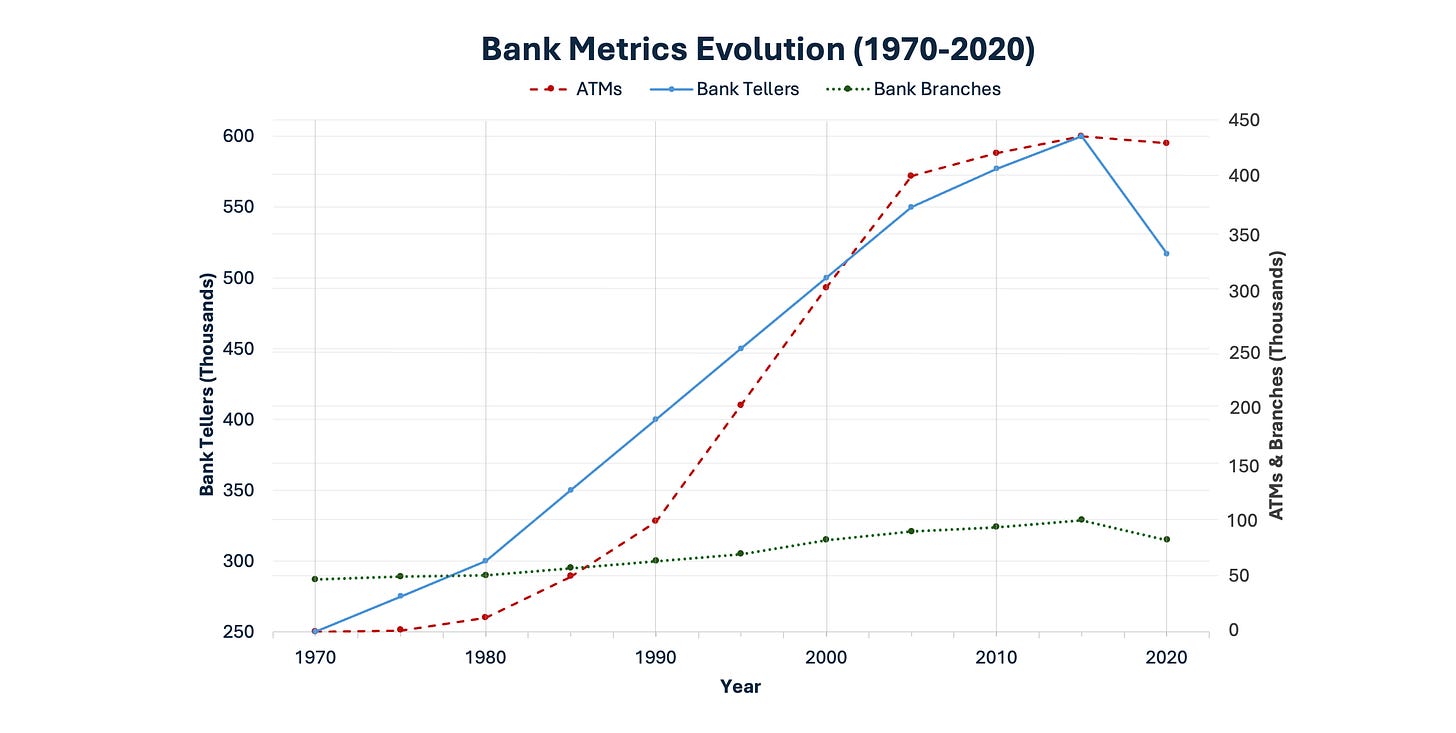

Autor’s canonical example is that of the automated teller machine (ATM) and the bank teller. When ATMs were introduced in the 1970s, many predicted that the bank teller would become obsolete. Machines could handle the core, routine task of dispensing cash far more efficiently than a person could. Yet between 1980 and 2010, the number of human bank tellers in the United States actually increased.

Two forces explain this. First, by automating cash handling, ATMs made it cheaper for banks to operate branches, which meant that more of them were opened. Second, and more importantly, the role of the teller was transformed. Freed from the repetitive task of counting cash, tellers could focus on more complex, relational work: building customer relationships, solving problems, and cross-selling higher-value services like loans, credit cards, and investments.

The technology augmented the value of the human part.

Modern Augmentation in Practice

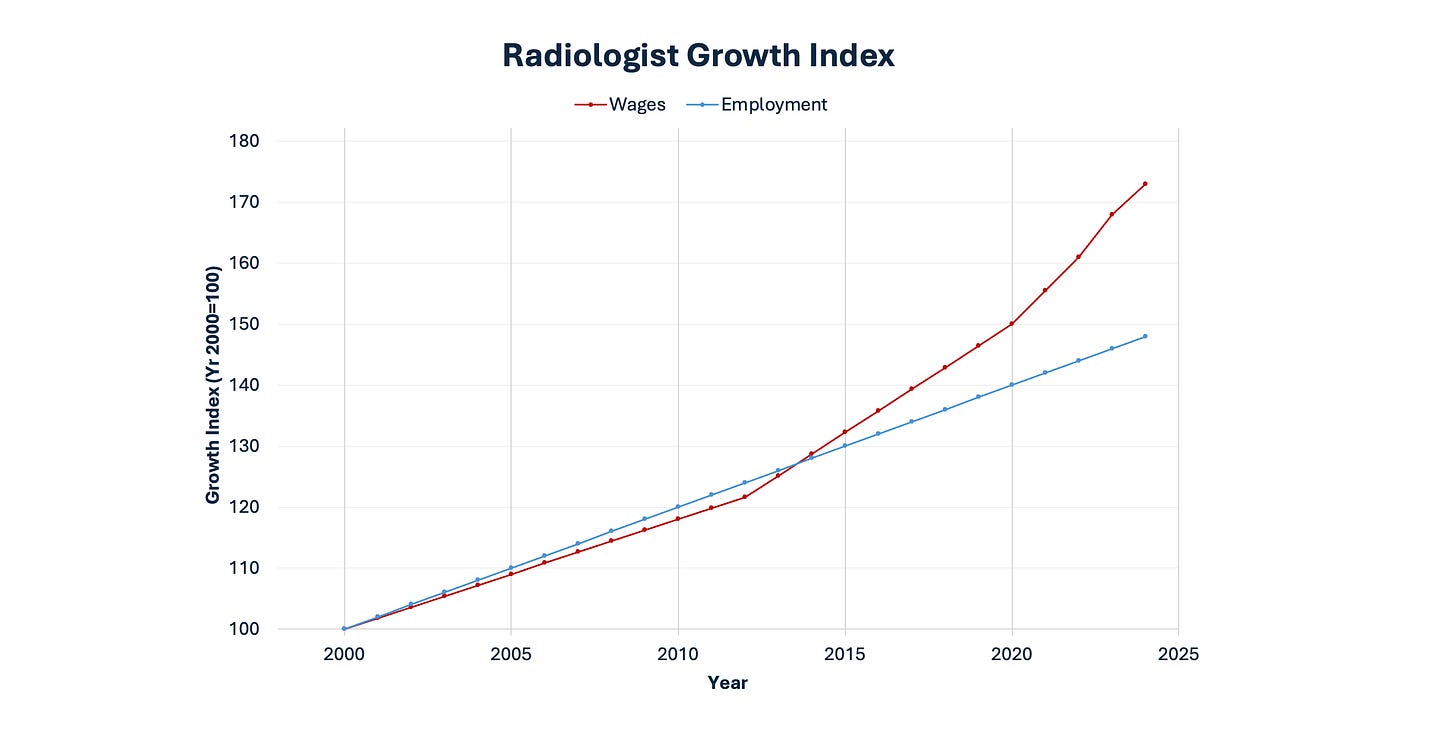

This principle of augmentation is at the core of the most successful technology deployments today. In radiology, AI models can now analyze thousands of medical images in seconds. They flag urgent cases like hemorrhages for immediate review. They detect subtle patterns of disease that may be invisible to the human eye.

As a result, the radiologist is freed to focus on the most complex diagnoses, consult with other physicians, and design treatment plans. The goal, as one expert noted, is an “expert radiologist partnering with a transparent and explainable AI system,” where the combination is better than either alone.

The outcomes are telling. Autor notes that employment in radiology has grown, not shrunk. More radiologists are employed today, and their wages have risen because their work is more sophisticated.

By contrast, while Uber put more drivers on the road, it pushed wages down by deskilling driving into a commodity task. Anyone with a smartphone and a driver’s license could now become a cab driver. Consequently, the job grew in quantity but declined in quality.

That is the difference between Quadrant 1 and Quadrant 4. One path elevates human expertise. The other path deskills and devalues.

Be a Talent Creator, Not a Job Killer

Healthcare today is one of the clearest examples of a Quadrant 1 and Quadrant 2 hybrid. It expands access to care while also augmenting clinicians. In places like China and India, the narrative around AI in health and education is largely optimistic. Why? Because they see it as a solution to shortages, not a threat to jobs.

The context matters. In the United States, the fear is often “Will AI take teachers’ jobs?” In parts of the developing world, the question is instead “Can AI help one teacher reach one hundred kids instead of thirty, because we simply don’t have enough teachers?”

When technology is framed as filling a critical gap or complementing human skill, resistance fades and adoption accelerates.

This brings me to a cautionary tale of what happens when leaders mishandle the human side of an AI rollout. A colleague told me about a Fortune 500 consumer goods company whose head of marketing was eager to deploy generative AI. The plan was to have AI produce all first drafts of marketing copy, including social posts and basic ad copies.

It was a solid idea. But the executive failed to create a plan on what role humans would continue to play. To the staff, the message sounded like this: “AI will soon write everything.” The copywriters naturally started whispering, “So… will we even have jobs next year?” Morale sank. Some quietly began job hunting, while others disengaged.

The irony is that the leader could have focused on the following message: “We are freeing you from routine drafts so that you can spend more time on bold creative ideas, on multimedia strategy, and on the new channels that we have long wanted to explore.”

Had he framed it that way, the team might have been excited. Instead, by failing to connect the dots, he sent the signal, “You are about to be replaced. Please assist your replacement.”

It was no surprise that the initiative stalled amid resistance. If you frame change as pure loss for your people, you guarantee they won’t be invested in making it succeed.

The Playbook: Six Non‑Negotiables

The failures and successes, from Toyota versus GM to Amazon Go to modern-day radiologists, converge on a clear conclusion: Technology adoption is not a tug of war between efficiency and humanity. It can, and should, be a flywheel where each reinforces the other.

Thankfully, certain companies are showing what it looks like to make people central to the plan as opposed to an afterthought or a PR gesture.

DHL coordinated with its works councils, the employee representatives, before rolling out AI tools. The process took longer, but it paid off with smoother implementation and agreed guidelines that quelled fears.

Accenture’s reskilling of 500,000 people shows that training at scale is possible when treated as a strategic priority. AT&T invested one billion dollars into retraining employees in new technology skills and guaranteed that anyone who completed certain programs would receive priority for new openings.

Unilever offers another model through its FLEX internal gig marketplace, where employees can rotate into departments that are growing. If a role is genuinely being phased out by technology, the company supports the affected employees to retrain for other positions.

Redeploying an experienced employee who already knows the business is almost always better than laying them off and hiring a stranger.

The question for every leader today is the same one that Toyota answered at NUMMI. It is not “What can this technology do?” Instead, it is “Who do we want our people to become?”

Here are six asks for meaningful automation:

Declare the human win up front (what gets better about the job).

Co‑design with frontline teams (DHL/works councils playbook).

Pledge no forced layoffs from automation (use attrition and redeployment).

Fund reskilling like a product (Accenture scale; set hours per FTE per quarter).

Build an internal talent marketplace (Unilever FLEX‑style rotations).

Set guardrails on surveillance (opt‑out paths, human escalation, and no “bossware”).

These are not acts of charity. They are strategic choices by companies that understand one fundamental truth:

You cannot build the future by declaring war on the very people who must create it.

See you again in two weeks. 👋

Howard, great article. I worked in automotive for 18 years and knew many of the good and bad automations firsthand, the struggles of the Detroit Big 3 in implementing the lean manufacturing system.

I like to hear your comment about the autonomous driving technologies that the society has collectively been spending so much money to solve. In my mind, if you want to improve efficiency and reduce accidents in the highly populated regions, you do high speed rail (HSR) systems like China or some large cities in Asia and Europe. For the less dense areas, you leave them to human drivers. Why are we spending so much time, money, and human capital to solve problems this way? Other examples include many of the proposed solutions using AI, crypto/blockchain, renewables/batteries, etc. All these things may have their valid use cases, but the tendency for Silicon Valley is to push them to the extreme for everything as the panacea. Remember back in 2021 the most frequent expression on Twitter is "Crypto will solve that" no matter what that is?

Enlightening and very well put. Loved it. Can I do a PhD with you?