Quietly Crushing It: Why Silent CEOs Keep Beating the Loud Ones

Hard data, brain science, and an Antarctic thriller reveal why quiet leadership is the real advantage.

More people would learn from their mistakes if they weren’t so busy denying them.

— Harold J. Smith

The era of the archetypal "loud" CEO is at its peak.

Elon Musk commands headlines with polarizing tweets and public feuds. His latest brawl with the U.S. President splashed across every headline.

Mark Zuckerberg, once a quiet coder, now says on a sold-out podcast stage that he’s “done apologizing.” Open AI’s Sam Altman accuses Zuckerberg on another podcast of poaching his people with offers of "$100 million signing bonuses and more [in] compensation per year."

Even Satya Nadella, the most “grown-up” of the bunch, tells Microsoft's AI tale in steady LinkedIn posts, week after week.

In today’s algorithm, volume masquerades as value. Any publicity is good publicity. The media feeds on it. Social platforms amplify it. Shareholders and voters seem to love it.

But are the loudest leaders really the ones we need most?

That question nagged at me, so I did what I always do when something feels off. I called someone who’s spent years studying what the rest of us overlook.

The Allure of Loud Leadership

Dr. Martin Gutmann is a historian turned business school professor. A soft-spoken Swiss American, he’s the kind of professor who lets a pause linger just long enough to make you uncomfortable, then drops something profound.

His 2023 book, The Unseen Leader, has quietly become a must‑read. His TED talk is a genteel broadside against what he calls “hero leaders.” It’s been viewed over 1.6 million times.

I asked Martin the question many of us wonder but rarely say out loud: Are we rewarding charisma at the expense of competence?

He told me:

Resist the temptation to confuse a good story with good leadership.

Exciting stories are usually the result of poor decisions. Good leadership makes drama disappear.

When a top executive makes headlines for heroically saving the day, Martin explained, it might be because they failed to quietly prevent the crisis in the first place.

To prove his point, he took me back to the early 1900s. This was a time of epic polar explorations.

(You can listen to our full conversation here, of course. But if you’d rather read on, I’ll sprinkle in research findings that make Martin’s argument even more compelling.)

A Tale of Two Poles

During the golden age of polar exploration, frostbite was the price of ambition. Glory was measured in flags planted on white nothingness.

While we talked, Martin turned history into parable. He showed me how easily we cheer on the wrong protagonist. Often we mistake drama for greatness.

On one side stands Sir Ernest Shackleton, the Anglo-Irish explorer lionized for his boldness and grit. His exploits read like an adventure novel.

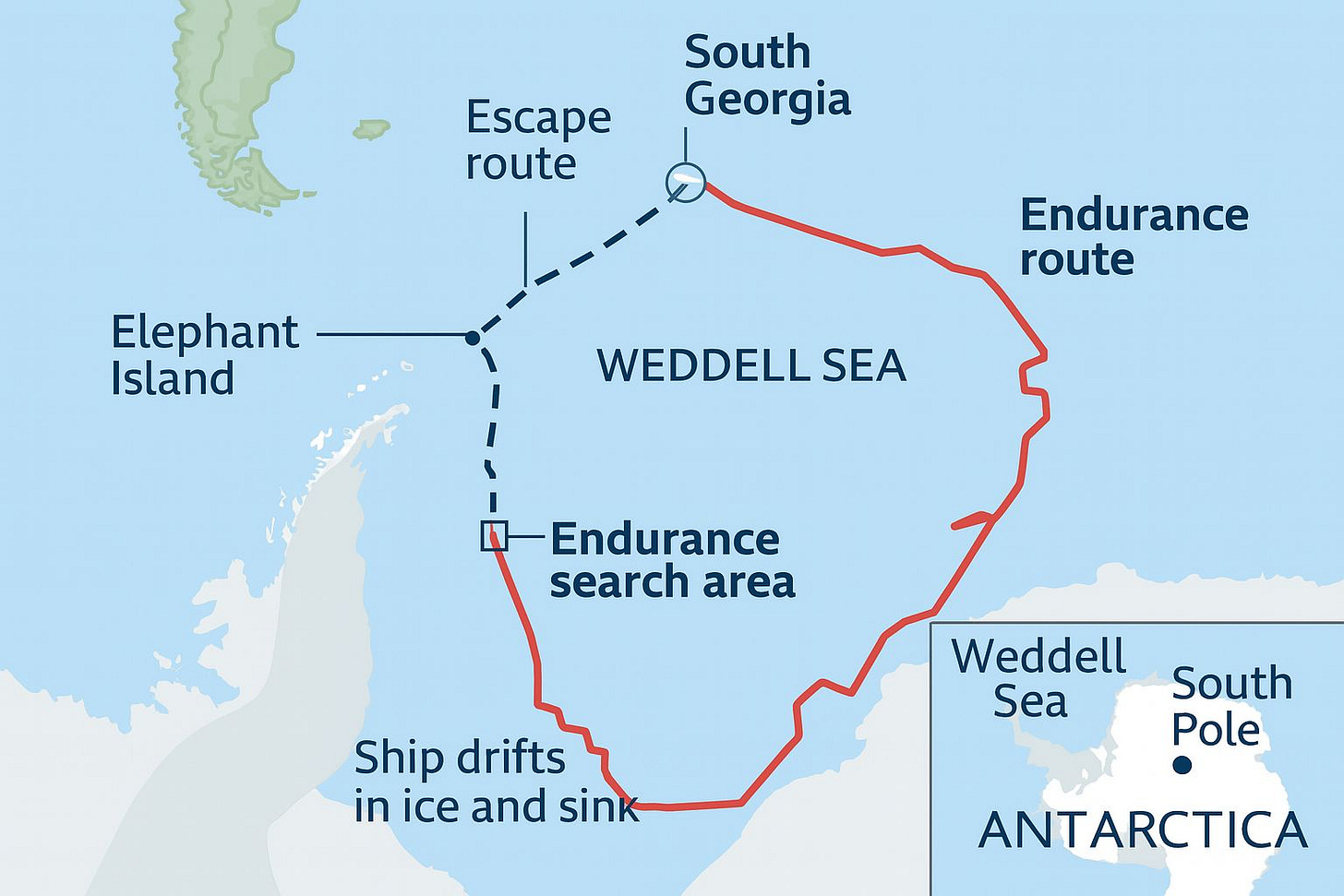

In 1914, he led the Imperial Trans-Antarctic Expedition, aiming to become the first to cross Antarctica via the South Pole.

Instead, his ship, Endurance, became trapped in pack ice in the Weddell Sea and was eventually crushed. Shackleton and his 27-man crew were stranded for months, facing starvation, frostbite, and utter isolation at the bottom of the world.

As Shackleton later wrote, “We fought the seas and the winds and at the same time had a daily struggle to keep ourselves alive.”

Then came the miraculous. He led all 27 men to safety after a months-long ordeal, culminating in an 800-nautical-mile journey in an open boat from Elephant Island to South Georgia. It remains one of the most extraordinary feats of seamanship and survival in history.

He never reached the Pole, but he brought every man home and became an instant legend.

The Loud Failure of Ernest Shackleton

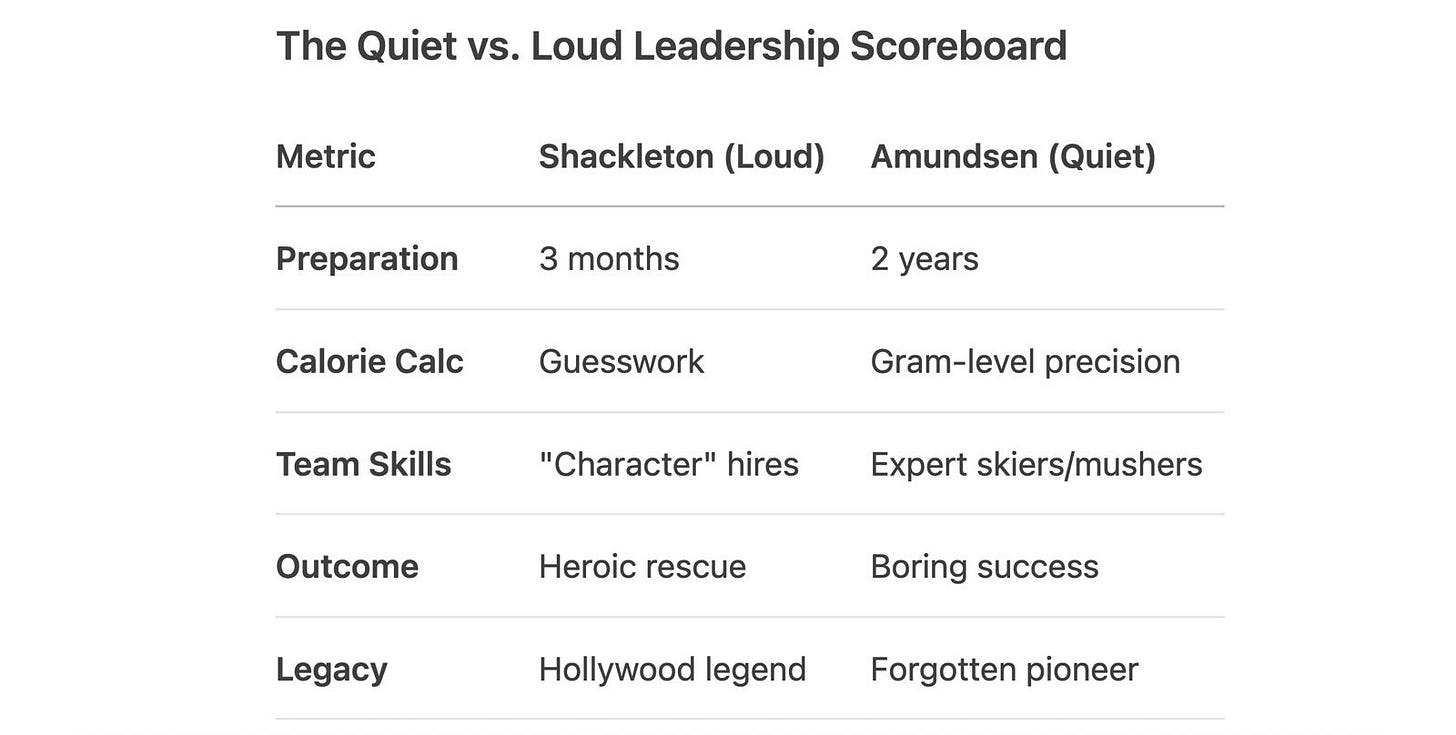

But pause. Look closer. This wasn’t just bad luck. Shackleton made a series of decisions that tilted the odds against him.

Martin put it bluntly:

If I were looking for an upcoming Hollywood movie, I would do it on Shackleton.

The ice crushes the ship, the crew camps on drifting floes, then mounts a daring open-boat escape. It’s gripping stuff, exactly the saga that fills business-school case studies and airport bookshelves.

The truth is less flattering.

Shackleton acquired Endurance at a bargain price after a Belgian backer went bankrupt. Though sturdy, the ship—built for Arctic cruises—wasn’t fully suited for the Weddell Sea’s ferocious pack ice.

He hired much of his crew through hasty, informal interviews, often favoring character or chemistry over polar experience.

And most damning of all: seasoned Norwegian whalers at South Georgia had warned him the Weddell Sea ice was unusually heavy that year.

He steamed ahead anyway.

The team was ill-equipped in critical ways: they underestimated calorie needs, wore subpar clothing, and lacked skiing skills.

Wrong ship. Wrong gear. Wrong team for the job. Ouch!

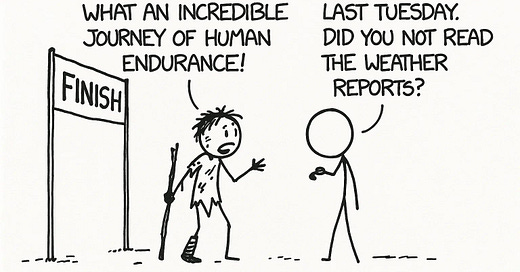

And yet, the crisis made Shackleton famous. “We celebrate turnarounds,” Martin said, “but gloss over the decisions that made a rescue necessary in the first place.”

Yes, Shackleton was a brilliant crisis manager, but across his four major Antarctic expeditions, not one achieved its original goal. Again and again, they fell short. Not because of fate, but because of mistakes that were foreseeable. Preventable.

“He wouldn’t have needed to be a savior if he hadn’t led his people into the crisis to begin with,” Martin dryly noted.

According to a recent survey, 64% of professionals feel overwhelmed by how quickly work is changing, and 68% are looking for more support to keep up. If you enjoyed this article and it brought you clarity, could I ask a quick favor?

Subscribe now. It’s free and takes just seconds to sign up.

You’ll join thousands of other ambitious managers and CEOs getting exclusive, research-backed insights straight to their inbox. Let’s keep you one inch ahead.

The Quiet Triumph of Roald Amundsen

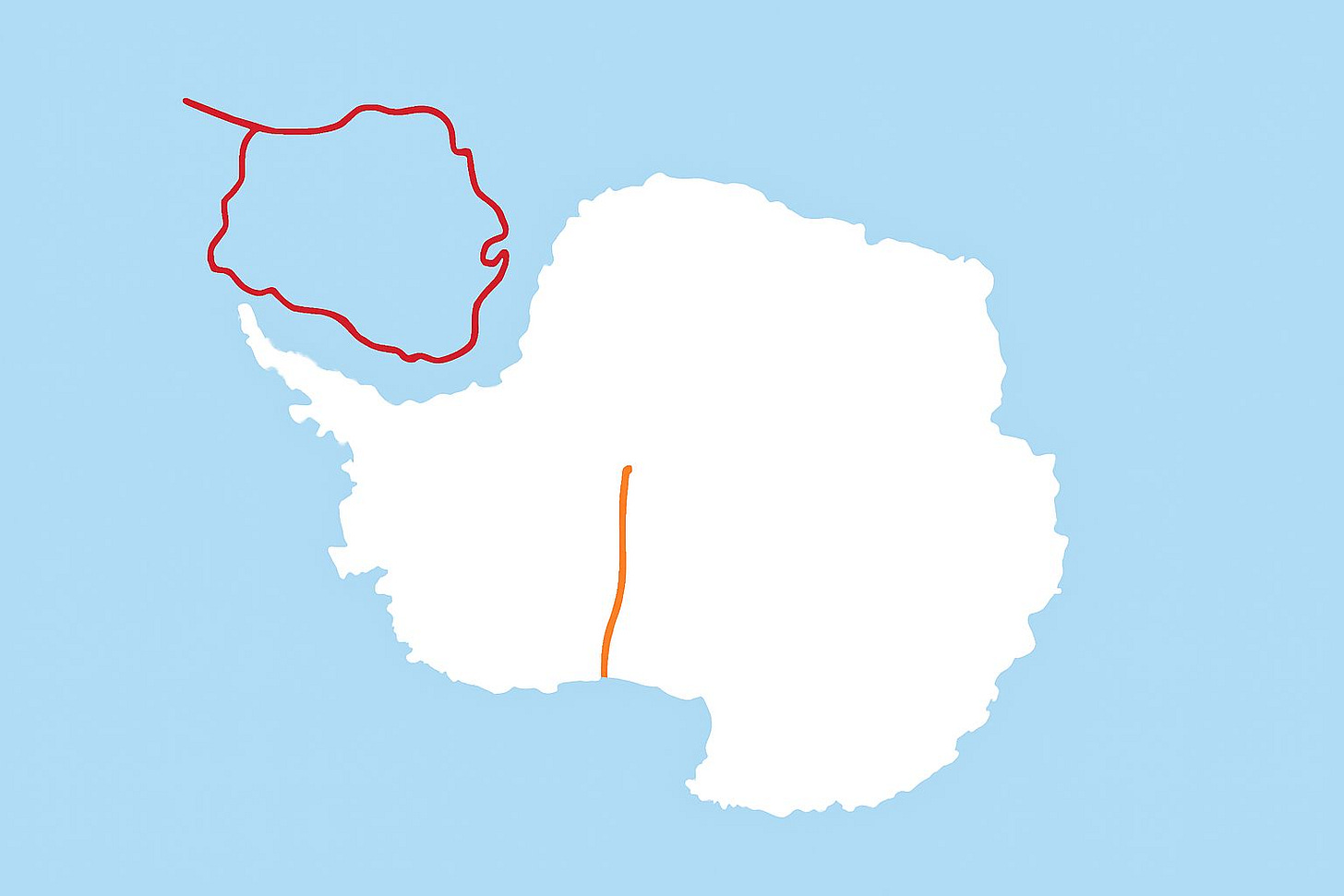

In contrast, Roald Amundsen’s name barely registers with most people. This methodical Norwegian reached the South Pole in December 1911, then quietly vanished from the spotlight.

No frostbite. No lost men. No drama.

Amundsen’s genius lay in his obsessive, almost monastic preparation.

Before even attempting the South Pole, he spent two years living among the Inuit during an Arctic expedition through the Northwest Passage. In the extreme north, he studied how Indigenous people survived the world’s harshest conditions. He copied what worked:

Reindeer fur parkas instead of wool.

Dog sleds instead of man-hauling.

Caribou skin boots that breathed instead of trapping moisture.

He trained his men not as explorers but as skiers and mushers. Everyone on his South Pole team could ski 20 miles per day with confidence. Food was pre-portioned and calorically calculated to the gram. No overpacking. No guesswork.

Where the British treated exploration like a noble endeavor, Amundsen treated it like a logistics problem.

Even his ship, the Fram, reflected his thinking. While the British favored coal-fired steamships that got stuck in ice, Amundsen equipped his vessel with a small diesel engine. Why? It would be quicker to start and easier to maintain.

And he made hard decisions. His dog teams weren’t pets. From the outset, he planned to cull weaker dogs to feed the stronger ones and, if needed, the men.

So, when he finally reached the South Pole—five weeks ahead of another British team—his men were healthy, efficient, and fully prepared for the return journey. They arrived back at base without incident.

Perhaps that’s why no one remembers him.

“If you read Amundsen’s diaries,” Martin told me, “they’re almost boring. No melodrama, no near‑death cliff‑hangers—just checklists, weather notes, and incremental progress. That’s what winning quietly looks like.”

Amundsen’s success was... boring.

Why the Boring Guy Wins But No One Recalls

In an environment where the ice doesn’t care about your ego, Amundsen made choices with surgical clarity. The British packed libraries and dynamite; Amundsen packed seal meat and skis.

But why do we—spectators, voters, shareholders—mistake rescue missions for visionary leadership? Why do we idolize those who brave the storm without asking whether they caused it in the first place?

Evolutionary psychology offers a clue. Our ancestors faced urgent coordination problems: organizing hunts, managing threats, migrating across hostile terrain. To survive, we evolved deep instincts to help us choose leaders.

Research shows we prefer more masculine-looking faces in times of war. Only in peace do we favor softer, more trustworthy features.

But today’s challenges aren’t saber-tooth tigers. Deep voices and tall frames have little to do with real leadership effectiveness in the modern world.

More troubling is how often the qualities we associate with charisma—confidence, boldness, vision—overlap with clinical narcissism. Think grandiosity. A hunger for admiration. A lack of empathy. These traits make narcissists shine in the spotlight. They look like visionaries. They sound like transformational leaders. But give them real power; the cracks show fast.

How? Overconfidence leads to reckless decisions. The need for admiration turns into compulsive attention-seeking. In fact, research shows narcissistic CEOs often hurt company performance. They make more aggressive (and poor) strategic bets, have lower-quality earnings, and tend to pay themselves excessively.

And when a crisis hits? They rarely take responsibility. The lack of empathy curdles into manipulation, cruelty, and betrayal of the very teams who elevated them.

In that regard, Shackleton wasn’t the worst. He wasn’t a narcissist. He cared deeply for his crew and did everything in his power to bring them home.

But how do we stop rewarding the wrong heroes?

The Team Managers Who Build Quiet Culture

Managers are the primary architects of a team’s micro-culture. One of the most powerful levers? Meetings.

Most meetings reward the loudest and quickest voices. Fast talkers dominate, while more reflective thinkers get sidelined. Ideas are judged not by their substance but by the confidence with which they’re delivered.

A manager committed to quiet leadership can rewire this dynamic. It starts with simple shifts:

Provide a clear agenda in advance. Define the objective of the meeting.

Make sure people have time to prepare, not just time to react.

Then, during the meeting:

Call on quieter team members explicitly.

Model curiosity over dominance.

Make it safe to say, “I don’t know.”

One famous example of this is Amazon’s “six-pager.” I first saw this in action not from a C-suite exec but from a few mid-level managers.

At the start of key meetings, everyone reads a six-page narrative memo in silence for the first 30 minutes.

No flashy slides. No winging it. Just clear, rigorous thinking—written in full sentences.

This quiet time forces preparation. It levels the playing field. It slows things down.

But more importantly, it de-emphasizes charisma and re-emphasizes clarity. Everyone begins with the same context.

You don’t need to overhaul company culture overnight, and anyone can introduce a small, steady hack. Create a refuge where thoughtfulness beats theatrics, and planning wins over posturing.

The evidence is clear: the archetypal “loud” leader, so often linked to narcissistic traits, imposes a steep toxicity tax on the rest of us. The obsession with a single heroic figure also breeds fragility. It creates dependency that undermines the collective intelligence needed for long-term success.

The Image I Cannot Unsee

Before Martin left me, he painted a picture that stuck:

"Imagine we're not talking about leadership but about crossing a wild river. There's hidden rocks, dangerous currents. One guy takes a quick look and says, 'I'm going for it!' Halfway through, he's getting yanked left and right, flapping his arms desperately, making all kinds of noise. Finally drags himself back to shore.

"We'll notice that guy. We'll say, 'Wow, he fought so hard! So brave!'

"Now imagine another swimmer who spent time understanding the river. Knows where the rocks are. Understands how the currents flow. Uses subtle movements to cross without any noise.

"If we even notice that swimmer, we'll probably say, 'Yeah, that looks pretty easy. I could do that.'"

He paused, letting his words sink in.

"That's leadership. The noisy swimmer gets the applause. The quiet one gets across."

In an era defined by complexity and unpredictability, noise is overrated. Volume isn’t virtue. Don’t clap for the guy still in the river. Follow the one who already crossed.

Lead quietly. Win loudly.

See you again in two weeks. 👋

Before I answer your question, I'd like to appreciate this lecture in newsletter content shape you've just provided.

Sadly, the loud one got the spotlight while the quiet ones were consistently understimated on almost every company I've worked.

This is an excellent illustration of the divide between blindly accepting what we are presented at face value versus the investigation of the background circumstances which caused the fraught scenario in the first place. Though historic, it lends itself well to highlight the massive difference in outcomes one may expect when using the contrasting methods of leadership.

Unforced errors are the worst kind, since they needlessly waste precious resources. Time, energy, effort, capital and goodwill cannot be directly or quickly recouped, putting the unfortunate party at a loss, or at least setting them on their back foot for a while. While delay is never the desired MO for a thriving business, employing thoughtfulness illuminates the opportune time and direction for action, affording greater returns reaching far beyond impulsiveness in the moment.

The skill of removing distractions and avoiding known challenges is so often overlooked until things are thrown into complete disarray and the effort becomes a rescue mission. Instead of hitting targets with ease, we risk being swept away, reduced to observing a riveting performance of “saviors” who may never have needed a call to action had we thoroughly considered the situation and implemented wise actions in advance.

Planning any grand endeavor merits time and bullet-proofing, if only to assure the team’s confidence in their ability to focus on the goal they strive to achieve. Critical thinking allows us to embrace the quiet dismantling of perilous circumstances ahead of their arrival and, instead, create supportive buffers. In this way, the methods and components of progress and success are not left up to chance, but are inherently included within the design itself.