Before Apple Disrupted Everything, Sony Did It First. Steve Jobs Never Forgot.

While everyone studies Apple's innovation playbook, they're missing the company that wrote it. Here is the untold story of how Sony taught Silicon Valley to disrupt.

Everybody gave me a hard time. It seemed as though nobody liked the idea … I do not believe that any amount of market research could have told us that the Sony Walkman would be successful. – Akio Morita, 1986

We do no market research. We don’t hire consultants … We just want to make great products. – Steve Jobs

In 1955, Sony’s CEO Akio Morita was offered the deal of a lifetime.

Bulova Watch Company stood before him with an offer any electronics maker would kill for: 100,000 units, immediate delivery, guaranteed payment.

Sony had just built Japan’s first transistor radio, a prototype called the TR-52. It was a marvel of miniaturization, but the first batch had a fatal flaw. The plastic grille warped in the summer heat. Still, America’s largest watch distributor wanted in. Bulova was ready to bring Sony’s technology to the United States.

There was only one condition.

“We’ll place the order,” the Bulova executives said, “but it will be sold as the Bulova radio. We want our brand name on it.”

Sony was still a tiny company. This single order would keep them alive for months. The revenue alone would be a breakthrough, but the chance to enter American distribution channels was priceless. From Tokyo, Morita’s board cabled him, urging him to take the deal.

Every rational calculation said the same thing: say yes.

Morita said no.

He later explained his thinking: “If we accept their order, they will be promoting the Bulova name. In five years, no one will remember Sony. But if I reject it and spend the next 50 years selling Sony-branded products in America, I will build a brand that will last for decades.”

The Bulova executives left the room shaking their heads. Morita’s own board questioned his sanity. Who turns down 100,000 units for the abstract notion of “brand building”?

That decision—betting on the unknown over the guaranteed—became the signature move of a company that didn’t just make products. Sony made desire.

The world didn’t realize it yet, but a new kind of company had just been born.

Disruption Rhymes

Today, every executive faces their own Bulova moment. Artificial intelligence is rewriting the rules of law, medicine, and filmmaking. Yet the father of modern disruption isn’t Sam Altman of OpenAI or Satya Nadella of Microsoft.

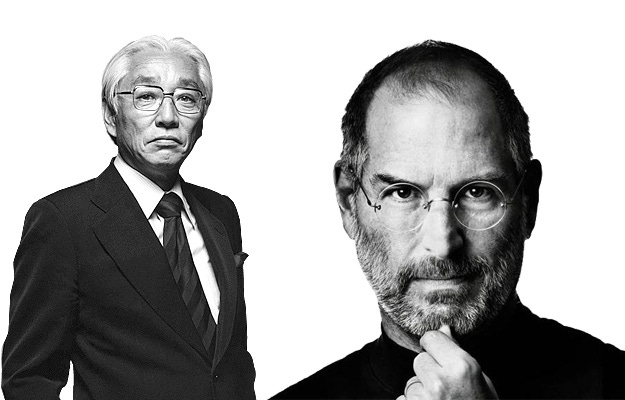

Before Steve Jobs studied disruption, there was Sony. Before the iPod, there was the Walkman. Before Apple Stores became temples of technology, Sony built its own in Tokyo and New York. Before “Think Different,” Morita was already showing the world how:

“I do not believe any amount of market research could have told us that the Sony Walkman would be successful. The Sony Walkman has literally changed the habits of millions of people around the world.”

Jobs would later echo Morita almost word for word: “It’s really hard to design products by focus groups. A lot of times, people don’t know what they want until you show it to them.”

No company captures the full arc of innovation quite like Sony, rising from a scrappy startup to a world-changing disruptor and, later, to a humbled giant. Its missteps in bloated diversification and a late struggle with software reveal how easy it is to lose your edge once success sets in.

Still, Sony’s early culture and its founder’s mentality offer a clear blueprint for the generative AI era. I spoke with someone who worked closely with Morita at the time. He described Morita’s restless curiosity, his belief in know-who over know-how, and his practice of rotating engineers through stores and factories. It created a company that was always learning, always moving, never standing still.

It’s a mindset every leader today could learn from. Born amid the ruins of postwar Japan, Sony built global brands, created new categories, and became the yardstick by which Apple once measured itself.

And the story of how Morita built it all, beginning in a bombed-out department store in Tokyo, still feels almost impossible.

A Postwar Startup Becomes a Disruptor

I first encountered Sony’s story in a Harvard Business School seminar. At the front of the room stood Clayton Christensen, the man who coined the term “disruptive innovation.”

“The puzzle I was trying to understand,” Christensen began, his voice measured and thoughtful, “was that most companies that are widely regarded as unassailable are found, a decade or two later, in the middle of the pack or at the bottom of the heap.”

He paused.

“I know a lot of CEOs,” Christensen continued, “and many are very smart for a very long time. When their firms collapse, everyone blames stupidity. But I don’t believe people’s intelligence swings that much.”

He told us about RCA, the titan of televisions in the 1950s. When RCA discovered transistor technology, the company faced a choice. They were making enormous profits on vacuum tube televisions. The early transistor was an engineer’s marvel, but it produced a low-quality, tinny sound.

For a company like RCA, whose brand was built on premium quality, why invest in an inferior technology for a low-margin novelty product?

First Principle: Market leaders excel at optimizing the status quo.

Disruption always starts on paths that look inferior to incumbents.

So RCA focused its transistor research on high-end applications, leaving the “toy” market for someone else to figure out. A little-known Japanese upstart called Sony paid $25,000 to license the transistor technology from Western Electric.

Sony, of course, couldn’t build a television with transistors. The technology wasn’t powerful enough. But they could build something smaller: a handheld radio. That first transistor radio’s sound quality was almost laughable. But it had one crucial advantage: You could carry it anywhere.

Teenagers snatched up these pocket radios by the millions. For the first time, young people could escape their parents’ living room and listen to rock ’n’ roll on their own terms. The sound quality didn’t matter. The freedom did.

RCA’s executives? They saw a joke. Low margins, lousy audio. Why bother with a bunch of kids with pocket change, they figured, when real profits came from selling big mahogany TV sets to grown-ups in suburbia?

Meanwhile, each generation of the transistor got a bit more powerful, a bit more reliable. Sony’s engineers weren’t asking, “How do we make a better vacuum tube?” They kept posing a different question: “What becomes possible as transistors improve?”

According to a recent survey, 64% of professionals feel overwhelmed by how quickly work is changing, and 68% are looking for more support to keep up. If you enjoyed this article and it brought you clarity, could I ask a quick favor?

Subscribe now. It’s free and takes just seconds to sign up.

You’ll join tens of thousands of other ambitious managers and CEOs receiving exclusive, research-backed insights delivered straight to their inboxes. Let’s keep you one inch ahead.

In 1963, Sony unveiled the “Tummy Television,” a tiny black-and-white portable TV priced for the masses. It was small enough to perch on your belly while lying in bed. The picture was grainy. The target customer? Young people in cramped apartments.

Second Principle: A disruptive innovation doesn’t need to be better by incumbents’ standards.

It just needs to be good enough to do a job that matters to someone new.

By the late 1960s, transistors were finally powerful enough for full-size color televisions. Who had spent two decades mastering the tech? Sony. In 1968, they rolled out the Trinitron, a color TV that didn’t just rival RCA’s best sets. It was superior. RCA suddenly found itself scrambling to catch up on a technology it had understood perfectly but chose not to pursue.

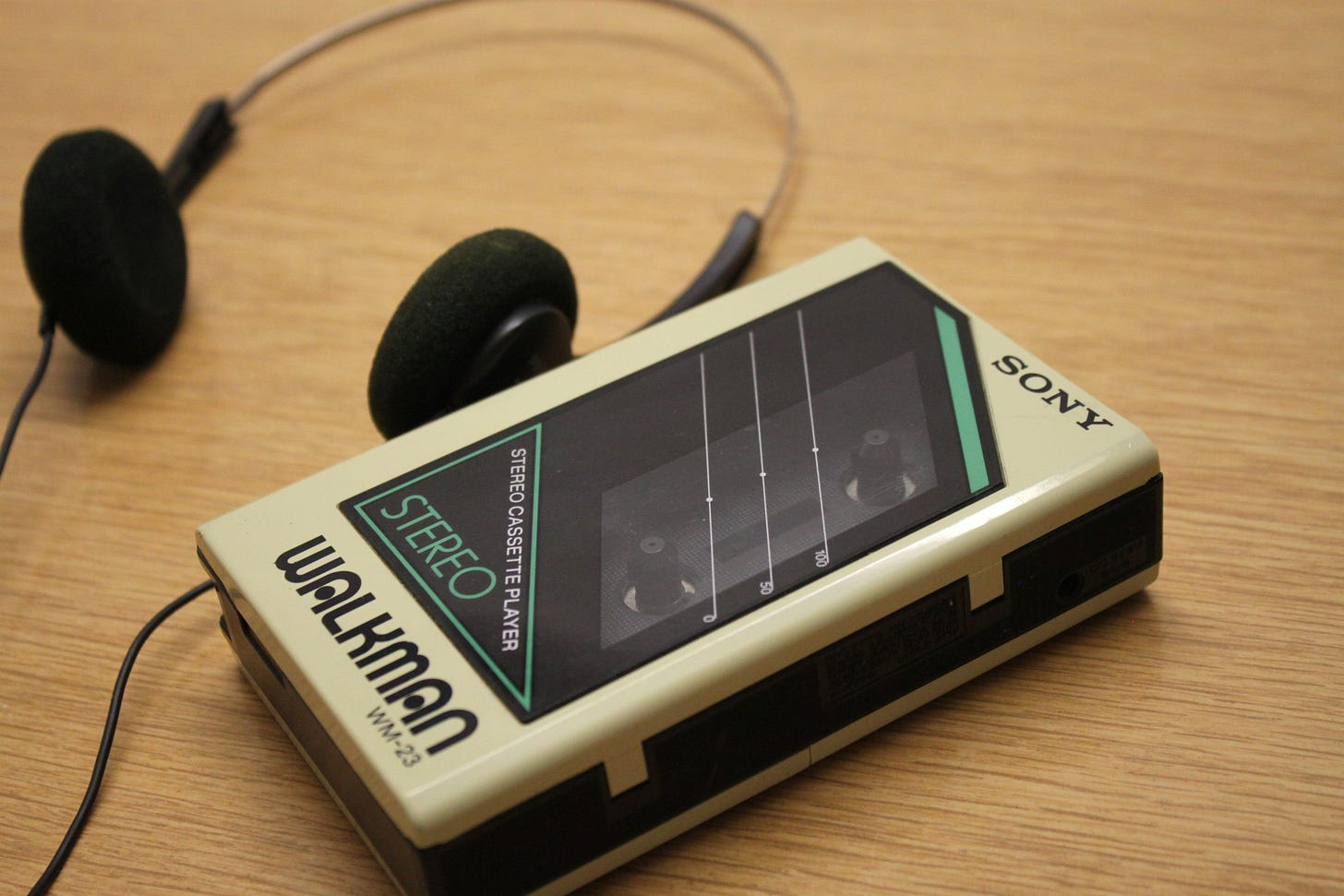

This pattern kept repeating. Fast forward to 1979: Sony introduced the Walkman, a portable tape player. Industry experts howled with laughter. People walking around with headphones on? They’d look absurd!

Twenty years later, Steve Jobs would obsessively study the Walkman as he developed the iPod. As Apple’s former CEO, John Sculley, recalled, “Steve’s point of reference was Sony at the time. He really wanted to be Sony. He didn’t want to be IBM. He didn’t want to be Microsoft.” Jobs even had a collection of Sony letterhead and marketing materials.

How Sony’s rise followed the disruptive-innovation playbook:

Enter markets the giants ignore.

Accept being worse by old metrics.

Win on new metrics that matter to new customers.

Improve relentlessly.

Return to the mainstream with a superior product.

By the time the incumbents notice, you’ve leapfrogged them with a better solution.

But there’s one thing disruption theory alone cannot explain: Why Sony?

Why not Panasonic, or Toshiba, or any of the other Japanese electronics firms that had access to the same technologies, the same manufacturing capabilities, the same markets?

The answer lies not in strategy, but in something far more organic. Call it intentional serendipity.

The Serendipity Engine

On August 15, 1945, Emperor Hirohito’s voice crackled across Japan’s airwaves. Few had ever heard their emperor speak. His message was devastating: Japan would surrender to the Allied forces.

For the first time in living memory, the nation had lost a war.

The devastation was total. American firebombing had obliterated 47% of Tokyo’s urban area. Half of the city’s residents were homeless. Japan wasn’t just economically in ruins. It was spiritually broken.

Amid this rubble, two engineers managed to find each other. Masaru Ibuka and Akio Morita decided to start a company. They set up shop in the bomb-scarred shell of a Tokyo department store with no electricity and no clear product idea. In their founding prospectus, they wrote that they sought “to establish a stable workplace where engineers could work to their heart’s content in full consciousness of their joy in technology and their social obligation.”

This wasn’t a business plan. It was a manifesto. And notice what’s missing: any mention of what the company would actually make.

The company was born out of pure creative defiance. Two young engineers refused to stop building and tinkering, even as everything around them lay in ashes.

Third Principle: Companies that harness serendipity don’t start with a fixed product roadmap.

They start with a question: “How do we create an environment where discovery becomes inevitable?”

Sony’s transistor radio was, in fact, a productive accident. When Western Electric announced it would license transistor technology overseas, Ibuka jumped at the chance, even though he had no idea what Sony might build with it. Morita himself flew to New York to secure the rights, knowing almost nothing about semiconductors.

It took two years of trial and error before Sony finally produced its first TR-52 prototype.

The pattern repeated in the 1980s, when Apple outsourced its PowerBook project. Sony canceled other initiatives to take on the challenge and freed up seven of its top engineers.

Working from just a half-page document of Apple’s specifications, Sony managed to cram the guts of a $4,500 Macintosh desktop into the form factor of a five-pound laptop. The entire project went from drawing board to production in only 13 months, astonishing Apple. One executive recalled, “That’s how it all started, our relationship with contract manufacturing.”

For Sony, it was more than a contract. It was a crash course in Apple’s industrial design discipline. Sony’s empire wasn’t built on a grand strategic plan. It was built on creating the conditions for happy accidents. Which raises one final question:

Why was Sony so much better at recognizing and capturing those lucky breaks?

The Know-Who Paradigm

I put that question to a researcher who closely observed Morita in the early days. His answer was unexpected: “Morita believed in know-who over know-how.”

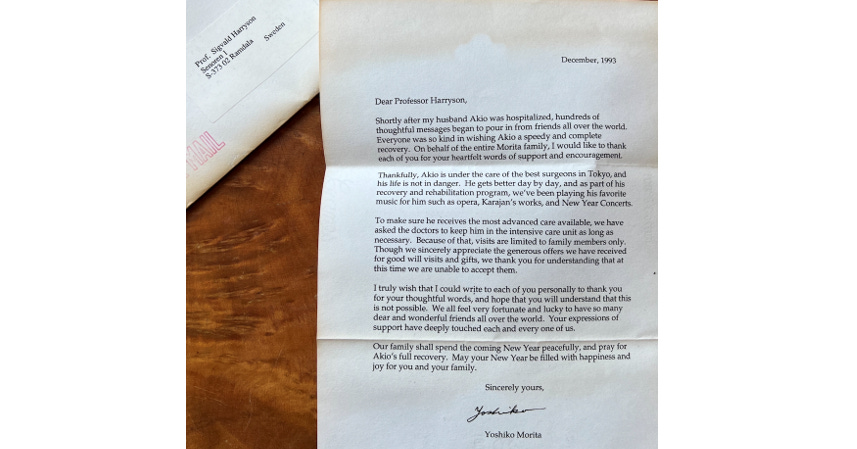

Dr. Sigvald Harryson is a Swedish researcher who had spent years inside Sony’s R&D labs since the early ‘80s. He interviewed 166 people, including CTO Makoto Kikuchi and, most remarkably, Morita himself.

“I had six carefully prepared questions for Morita,” Harryson told me, his eyes lighting up at the memory. “I was ready to understand Sony’s innovation system, their R&D process, their strategic planning frameworks.”

“What did he tell you?” I asked.

“His answer to every question was the same: ‘The more people you know, the better it is.’”

It took Harryson seven months to understand what Morita was really saying. The insight came when he studied how Sony actually organized its engineers.

Sony institutionalized curiosity through rotation. Engineers were not allowed to remain in R&D indefinitely. “People who stay in R&D are waste,” CTO Kikuchi told Harryson. “If somebody needs to stay more than two years, they haven’t performed.”

New hires spent six months in the lab, six months in manufacturing, and six months selling products in flagship stores.

Only then did they return to R&D for two years. After developing a product as more seasoned engineers, they moved back to manufacturing to oversee production, then to retail to sell what they had designed.

That last step mattered. They had to sell the thing they built.

Fourth Principle: Deep expertise without cross-functional empathy produces elegant irrelevance.

Sony engineered empathy into its career paths.

But Sony went further. Every week, they held “stand-up beer parties.” These were massive gatherings where hundreds of employees from different divisions mixed socially.

“The guy from R&D would meet the colleague from manufacturing and from sales,” Harryson explained. “They would stay connected across organizational boundaries.”

A senior VP explains a circuit board problem to a line worker. Two engineers from completely different product lines sketch ideas on napkins. You’re not ‘R&D Tanaka-san’ or ‘manufacturing Sato-san’ at these parties. You’re just Tanaka. Just Sato.

Fifth Principle: Organizational innovation requires defeating the natural entropy toward specialization.

Sony weaponized social connection against functional silos.

This philosophy of connection extended far beyond Sony’s walls.

When Sony pioneered the CD format with Philips in the 1980s, it wasn’t just a case of technology transfer. It was the first time a major Japanese electronics firm had conducted research as an equal partner with a European company.

Sony sent its engineers to Eindhoven for years, working side by side with Philips researchers.

The result? Sony brought the CD to market much faster than Philips. Not because they had better technology—they had co-developed it—but because their organization could move knowledge from lab to factory to market with unprecedented speed.

I pressed Harryson on Morita’s personal role: “What was he really like?”

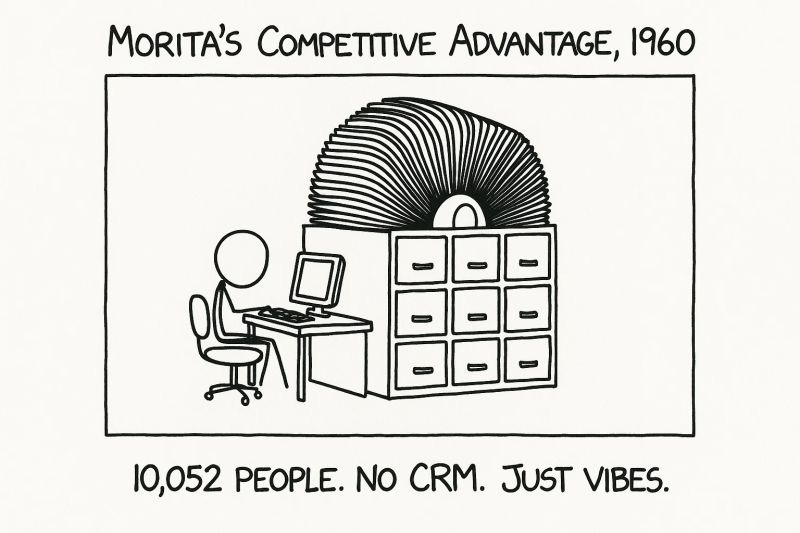

“His English was quite good, better than most Japanese executives,” Harryson recalled. “But what struck me most was his genuine curiosity. He didn’t just meet people; he remembered them. When I left our meeting, his secretary entered me into his database. I was person number 10,052.”

“Ten thousand people?”

“At least. And he stayed connected. Seven months later, I received a letter from Mrs. Morita. Her husband had fallen ill. She was likely writing to many in his network, and it made me understand, in a much deeper way, the true value of know-who over know-how.”

The Decline and the Lesson

Sony’s golden era couldn’t last forever. Akio Morita retired as chairman on November 25, 1994, a year after a stroke that left him weakened. By the 2000s, the company had lost its way. The television division bled money for eight straight years. Its mobile phones were an unmitigated disaster. The Vaio PC line faltered and was eventually sold.

What happened?

The world had changed in a fundamental way Sony didn’t anticipate: Everything became a computer.

Sony’s engineers were brilliant at hardware. But they never developed deep software expertise. They thought of content as “software,” which is why they bought music labels and movie studios. But they never grasped computational software, the operating systems, cloud services, and AI—the entire digital substrate that now powers consumer electronics.

Final Principle: Know-who only works if you’re asking the right “who.”

Sony built networks of hardware engineers when the future belonged to software engineers.

Sony’s history reminds us that the most important disruptions often start at the fringes, that failure is part of the journey, and that innovation is, at its core, a human network.

The most striking thing about Sony’s golden era isn’t the products they made or the markets they created. It’s the connections that made them possible.

But connection is a muscle. Stop exercising it and it atrophies.

Today, Apple, Microsoft, and Nvidia thrive because they’ve learned their own variations of the same playbook.

They have succeeded by being open rather than closed, by rotating people when specialization was the norm, by valuing who you know over what you know, by sharing innovations instead of hoarding them, by creating products nobody asked for rather than simply listening to customer demands.

Morita was right: The more people you truly know, deeply understand, and authentically connect with, the better it gets.

Because the future doesn’t belong to those with the best plans. It belongs to those with the best questions and the best people to explore them with.

Morita kept a database of 10,000 people. How many are in yours?

The rotation system you described is exactly what made Sony so adaptable in the hardware era. Engineers who understood manufacturing constraints and retail realities built products that actually worked in the real world. But that same system became a liabilty when software started eating hardware becuase you can't rotate someone through a six-month coding sprint and expect them to understand software architectures. The know-who philosophy works brilliantly until the who you need to know fundamentally changes.

I re-tell a story I heard, and it overlaps this topic. That Morita set five different teams to each inventing the VCR, basically had them compete. I forget whether the one team "won" or if things from different teams were then combined into the final design, but the point was that it wasn't a top-down decision, of what to work on, what to do. It came up out of the ranks trying different experiments.

In that sense, it was much closer to a "Libertarian" company than any that are run by alleged Libertarians. Mark Zuckerberg didn't set ten teams to working on "What's the Next Big Thing" for Facebook; it was a top-down decision to invent the Metaverse, which tanked and blew away an insane $20B in R&D.

A true Libertarian would run a company with 3 marketing departments, which would compete to get the nod for their campaign; maybe a few HR departments, so employees could pick the one that did the most for them. But nooooo...all of their corporate Org charts are pyramids that don't look different from the Court of Versailles; everybody has one Boss, who totally controls their actions, all the way down to the bottom.

Morita is the only one I've heard of that I can honour for having a view anything remotely like giving employees "liberty" to invent.